-

Brand Equity

Brand Equity

Zen versus i-Pod

Benefits

Loyalty Pyramid

NPI, NAI

Brand Equity Models

Brand Equity Index

Brand Equity Drivers

Analysis and Interpretation

Overview

- Brand Sensing

- Brand Equity

- Marketing Education

- Is Marketing Education Fluffy and Weak?

- How to Choose the Right Marketing Simulator

- Self-Learners: Experiential Learning to Adapt to the New Age of Marketing

- Negotiation Skills Training for Retailers, Marketers, Trade Marketers and Category Managers

- Simulators becoming essential Training Platforms

- What they SHOULD TEACH at Business Schools

- Experiential Learning through Marketing Simulators

-

MarketingMind

Brand Equity

Brand Equity

Zen versus i-Pod

Benefits

Loyalty Pyramid

NPI, NAI

Brand Equity Models

Brand Equity Index

Brand Equity Drivers

Analysis and Interpretation

Overview

- Brand Sensing

- Brand Equity

- Marketing Education

- Is Marketing Education Fluffy and Weak?

- How to Choose the Right Marketing Simulator

- Self-Learners: Experiential Learning to Adapt to the New Age of Marketing

- Negotiation Skills Training for Retailers, Marketers, Trade Marketers and Category Managers

- Simulators becoming essential Training Platforms

- What they SHOULD TEACH at Business Schools

- Experiential Learning through Marketing Simulators

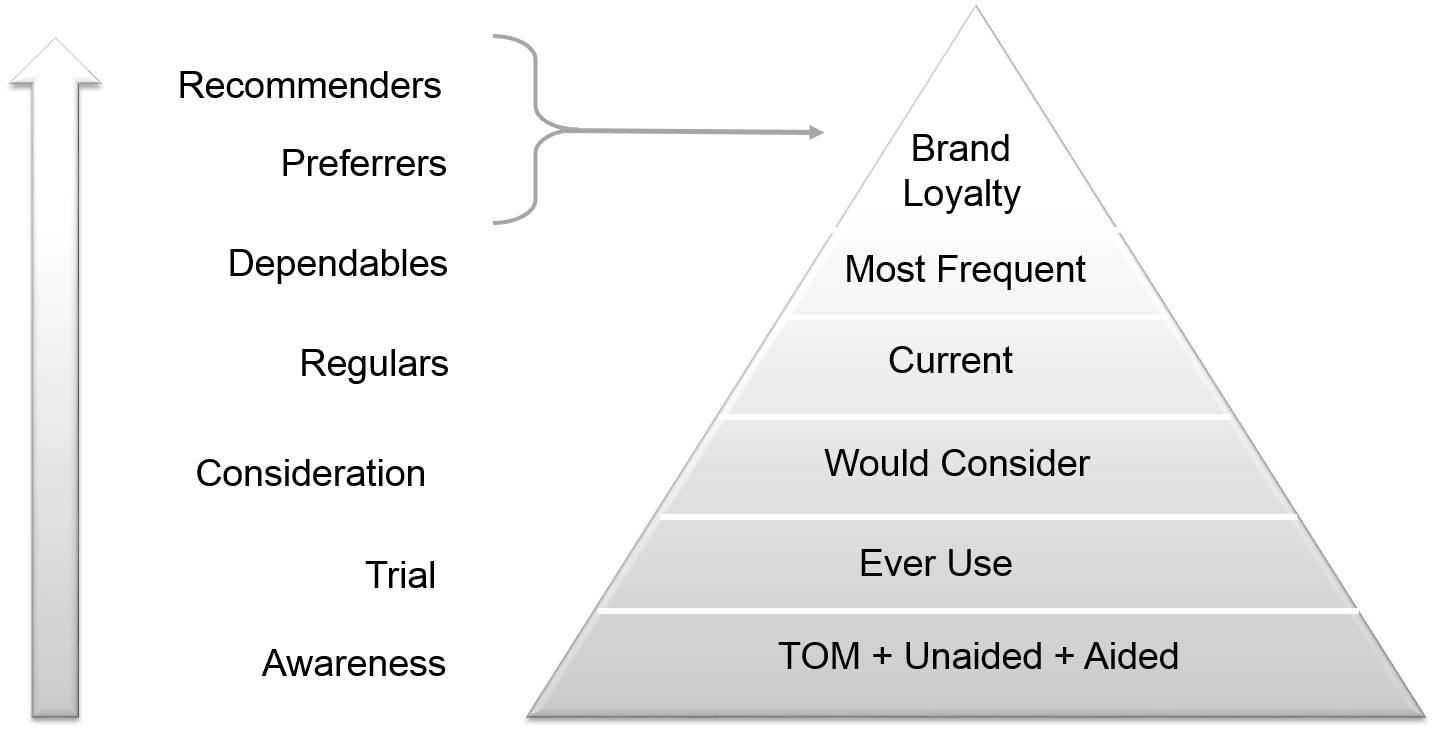

The Loyalty Pyramid

Brand loyalty, as stated earlier, is one of the core benefits or outcomes of brand equity. It is reflected in the manner consumers engage with a brand and may be assessed in terms of the hierarchy of levels of engagement depicted in Exhibit 2.2. Consumers at the base of this loyalty ladder or loyalty pyramid are aware of the brand; it achieves a presence in their minds. Moving up, the brand is of relevance to consumers who have tried it, or who consider buying it.

Consumers who regularly buy the brand are referred to as regulars, and those who buy it most often are called dependables. These are behaviourally loyal consumers who drive brand performance.

The pyramid gets thinner from the base to dependables. Trial is a sub-set of awareness, consideration is a sub-set of trial, regulars is a sub-set of consideration, and dependables is a sub-set of regulars.

Brand loyalty represents the highest level of engagement with a brand. Loyal consumers have high level of affinity with the brand; they consider it as their favourite and are willing to recommend it to others.

Brand loyalty is a state of mind, not a behavioural outcome. A consumer is brand loyal if she has a positive, preferential attitude towards the product or service. Attitudinal loyalty, emotional loyalty and brand loyalty are interchangeable terms that allude to this state of mind.

Behavioural loyalty, unlike emotional loyalty, is specifically a behavioural outcome. Defined as brand share amongst brand buyers, it is the quantity of brand purchases by the individual or household as a percentage of total category purchases. For instance, if a consumer drinks 40 cups of Nescafe and 10 cups of other brands of coffee, her behavioural loyalty to Nescafe is 80% over that period of time.

The proportion of consumers that are brand loyal is usually less than those that are dependables, but this is not always the case. Brand loyalty does not always translate to high behavioural loyalty. Availability, affordability and convenience may be constraining factors. For instance, consumers may not be able to buy a preferred brand because is it not available at their regular store.

Similarly, high behavioural loyalty need not be the outcome of brand loyalty. In the case of services like retail banking, due to the inconvenience that it causes, there is reluctance to switch from one service provider to another. Because of reasons such as these, and inertia in general, a customer may continue using a service even after there is erosion in her affinity for the service provider.

Interpreting Loyalty Pyramid Data

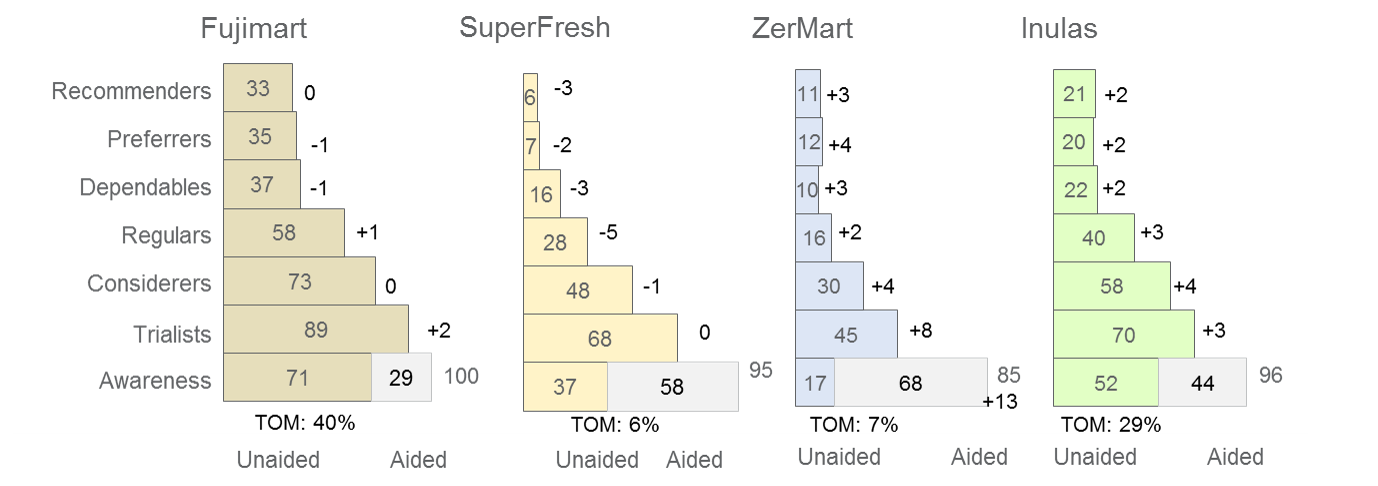

In the context of loyalty pyramids, fatter is better. The shifts up and down the adjoining levels of the loyalty pyramid reveal the strengthening and weakening of the brand’s interaction with consumers. Comparisons across brands reveal peculiarities that highlight their strengths and weaknesses.

Take for instance the information presented in Exhibit 2.3, which depicts four supermarket banners — Fujimart, SuperFresh, ZerMart and Inulas. The numbers on the right of the bars, with positive and negative signs, reflect the change over previous period. Fujimart for instance has increased its base of regular shoppers from 57% in the previous time period to 58% (+1). For this chain there appears to have been a 1%-point shift upwards from considerers to regulars.

Brand awareness is the percentage of consumers who claim they are aware of the brand. It is gauged on three planes — top-of-mind (TOM), spontaneous (unaided) and aided. Top-of-mind awareness is the first brand that comes to mind. Spontaneous or unaided awareness is brand recall without prompting, and aided awareness is brand recall with prompting.

The structural differences between the loyalty pyramids of the banners in Exhibit 2.3 reveal some of the opportunities and challenges they confront. For instance, compared to SuperFresh, ZerMart has much lower base of regular shoppers and a significantly higher base of recommenders and preferrers, reflecting relatively weak behavioural loyalty and strong emotional or attitudinal loyalty. This suggests that while shoppers are attracted, there appears to be some hindrances to shopping at ZerMart.

With only 17% unaided awareness, ZerMart is weak on salience. The data suggests that it is a small, growing banner that offers some distinct advantages over competing stores. This is reflected in the high flow from regular shoppers to dependables and recommenders. However, as yet it is not a well-known banner.

Though the pyramid does not reveal the factors driving its growth, ZerMart clearly appears to be on high trajectory. Considering its small base, the increases at all levels of the loyalty pyramid are quite large. For instance, preferrers shot up from 8% to 12%, reflecting a large 50% increase.

Fujimart is exceptionally strong commanding 40% top-of-mind awareness, and very high behavioural and emotional loyalty. Inulas is the second largest banner and is experiencing high growth. SuperFresh, on the other and is experiencing considerable erosion, particularly in regular shoppers.

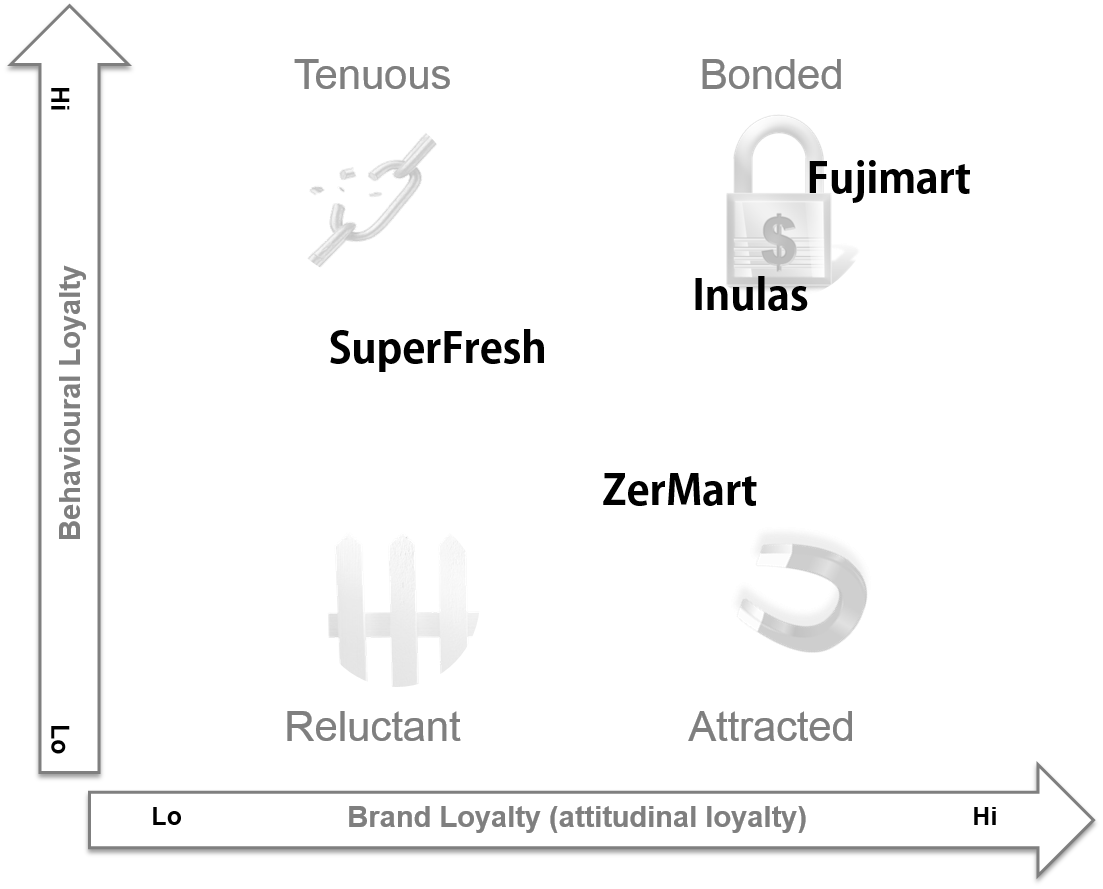

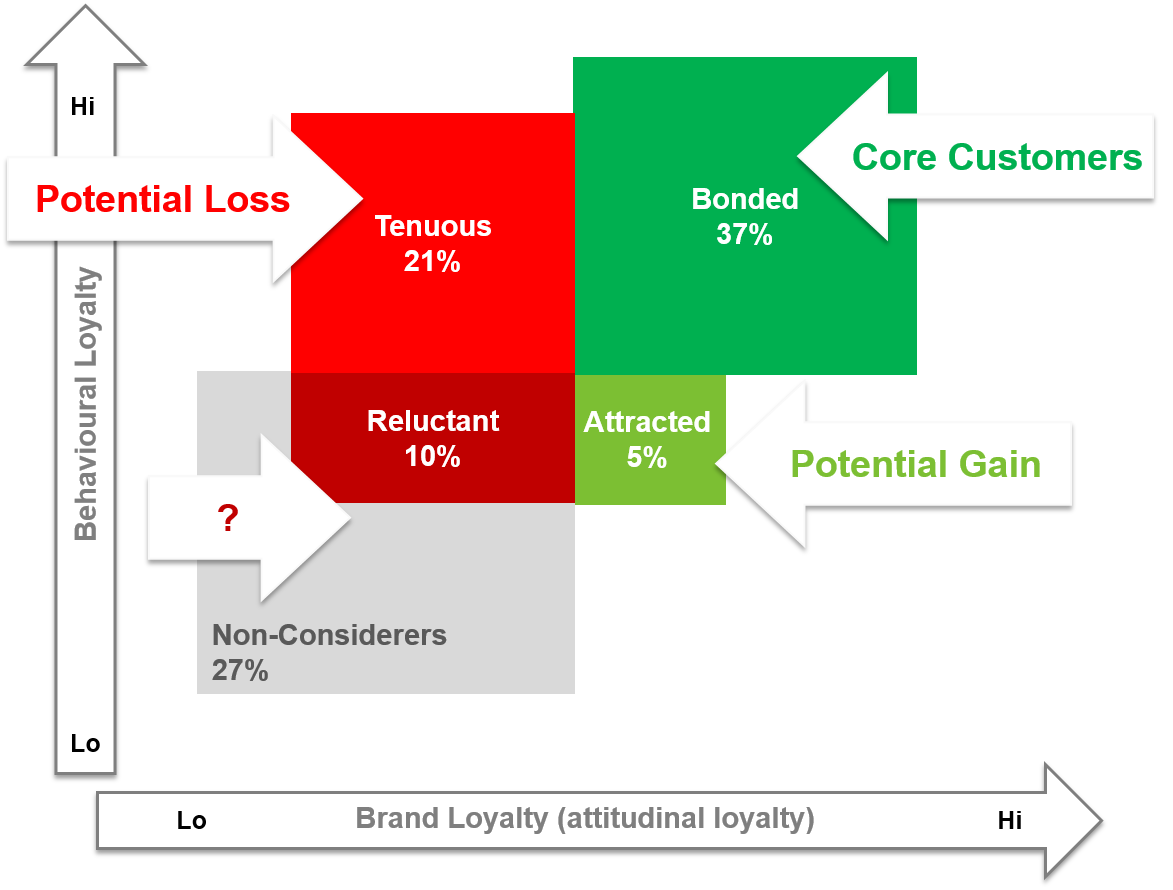

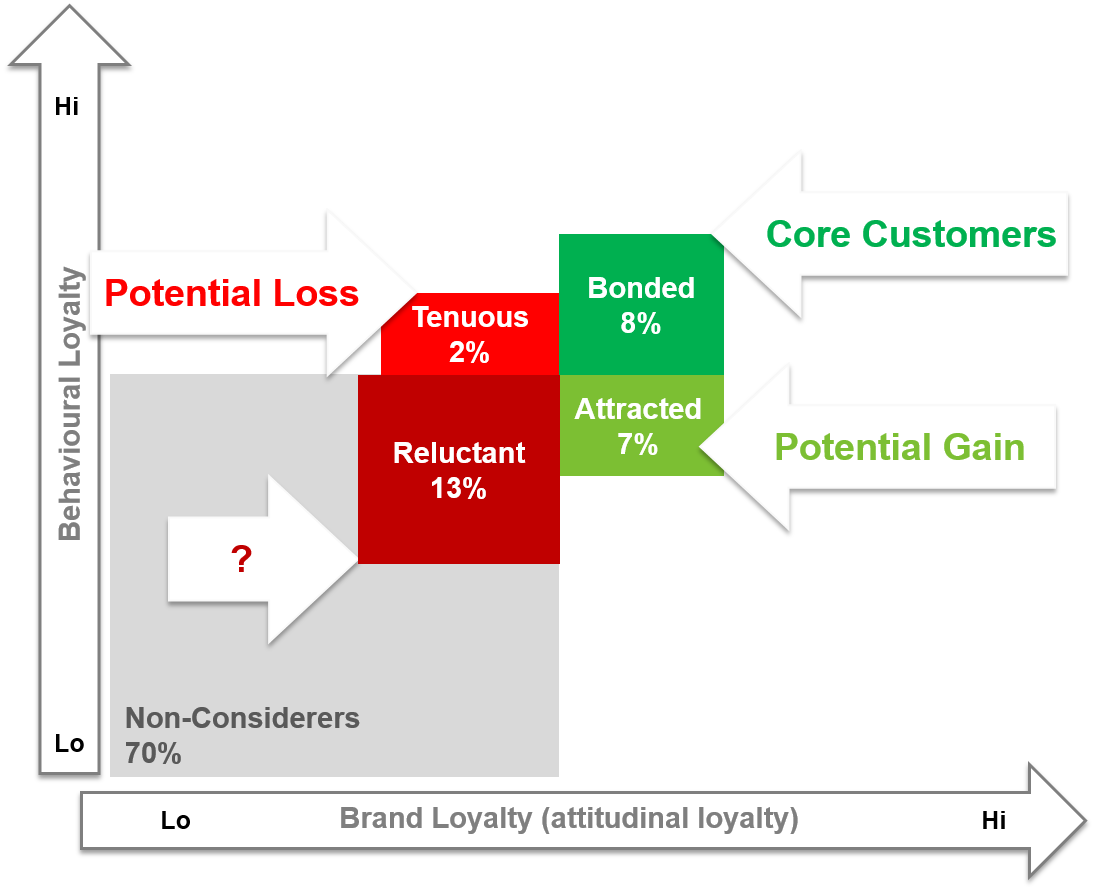

By examining their attitudinal and behaviour loyalty for a brand, each of the respondents may be placed into one of four quadrants of the loyalty matrix (Exhibit 2.5):

- Bonded: Customers who are both attitudinally loyal (recommenders or preferrers) as well as behaviourally loyal (regulars).

- Attracted: Customers who are attitudinally loyal, but not behaviourally loyal.

- Tenuous: Customers who are behaviourally loyal, but not attitudinally loyal.

- Reluctant: Customers who are neither attitudinally nor behaviourally loyal.

The loyalty matrix depicted in Exhibit 2.4 serves as a conceptual summary of how the banners compare with one another. Exhibit 2.5 provides a breakup of Fujimart and ZerMart shoppers across loyalty segments. Fujimart has relatively high bonded shoppers who exhibit both behavioural loyalty and attitudinal loyalty. ZerMart on the other hand, relative to its base of considerers, has a fairly large base of shoppers who are attracted — they exhibit attitudinal loyalty but are not behaviourally loyal.

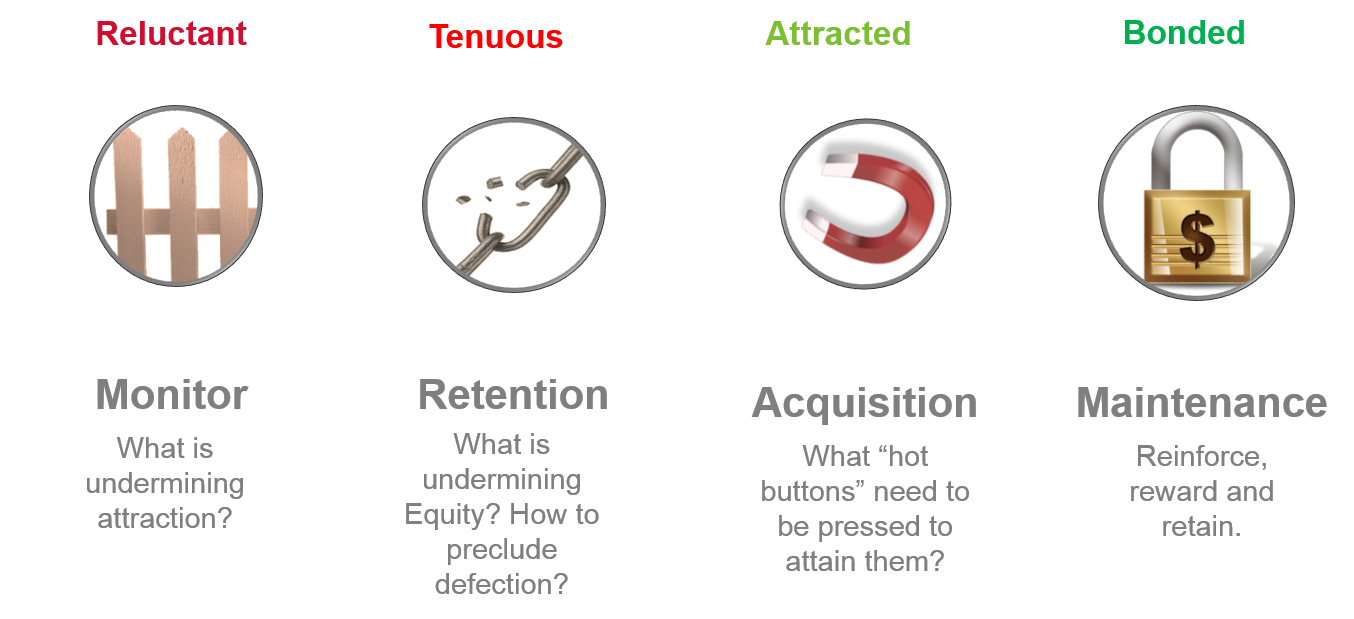

This categorization is useful in tailoring marketing efforts and strategies to cater to the distinct requirements of each segment (refer Exhibit 2.6).

With bonded shoppers, the marketing priority is to keep them bonded by reinforcing the aspects of the offering that these consumers value, and by rewarding them for their loyalty. For the attracted, acquisition is the goal. Marketers need to determine what “hot buttons” to press to get these customers to embrace their brand. Tenuous shoppers need to be retained. One needs to understand what undermines their brand loyalty and identify ways of precluding defection. The reluctant and the non-considerers need to be monitored. In order to target them, marketers need to find ways of attracting them.

While the loyalty pyramid and the loyalty matrix analysis reveal some of the strengths and weaknesses of brands, and some of the issues confronting them, additional information is required to chalk out strategies that address these issues. In particular, to identify what undermines brand equity, we need to measure it, and understand what drives it.

A practical approach to measuring brand equity is through its outcomes. If a brand has a large base of loyal consumers, or if it can command a price premium, one may conclude that it possesses high equity.

Previous Next

Use the Search Bar to find content on MarketingMind.

Contact | Privacy Statement | Disclaimer: Opinions and views expressed on www.ashokcharan.com are the author’s personal views, and do not represent the official views of the National University of Singapore (NUS) or the NUS Business School | © Copyright 2013-2026 www.ashokcharan.com. All Rights Reserved.