-

Articles

- Marketing Education

Is Marketing Education Fluffy and Weak?

How to Choose the Right Marketing Simulator

Self-Learners: Experiential Learning to Adapt to the New Age of Marketing

- Negotiation Skills Training for Retailers, Marketers, Trade Marketers and Category Managers

Simulators becoming essential Training Platforms

What they SHOULD TEACH at Business Schools

Experiential Learning through Marketing Simulators

-

MarketingMind

Articles

- Marketing Education

Is Marketing Education Fluffy and Weak?

How to Choose the Right Marketing Simulator

Self-Learners: Experiential Learning to Adapt to the New Age of Marketing

- Negotiation Skills Training for Retailers, Marketers, Trade Marketers and Category Managers

Simulators becoming essential Training Platforms

What they SHOULD TEACH at Business Schools

Experiential Learning through Marketing Simulators

How to Choose the Right Marketing Simulator

The top 10 factors you must consider

Exhibit 1 Marketing simulators like Destiny that impart much needed combat experiences, should become essential training platforms for marketing professionals.

It takes several years of practice for marketers to acquire the skills to succeed in the battleground of consumer markets. Only then can they be trusted to take strategic decisions that shape the future of mega brands and banners.

From a learning standpoint, this begs the question, how can we speed up the process of developing future marketing and retailing leaders? Is it possible to use automation to impart the experience of consumer marketing?

Marketing simulators are being developed in response to these questions. By replicating consumer behaviours, authentic simulators offer a holistic learning experience for marketers. They should become essential training platforms for marketing professionals, filling the void between the theoretical concepts taught in business schools and the practical knowledge required in the industry.

There are already numerous options available as you will see if you google. Unfortunately, the vast majority of these are merely games that masquerade as simulators.

Educators and self-learners therefore need to be careful that they choose the right simulator. This article written by the developer of the Destiny marketing simulator (Exhibit 1), outlines the important factors and the main watchouts that need to be considered.

1. Authenticity

Simulators must accurately reflect reality. Above all else, this is crucial. Imagine what could happen if pilots were trained on flawed flight simulators or if surgeons honed their skills on inaccurate surgical simulators.

Lacking authenticity, fake market simulators imbue the wrong gut instincts! In the worst-case scenario they could impair your judgement and harm your brands.

Often it is easy to spot fakes. They look like toys, feel like toys and act like toys. However, there also exist plenty of sophisticated looking simulators and the black box that controls these devices is concealed. They seem logical to the untrained eye, but do they replicate real market complexities?

The difficulty with marketing simulators is that unlike those that perform physical tasks like surgery or piloting a plane, it is hard to determine their authenticity. There are too many variables that influence the outcome, making the logic difficult to scrutinize.

If a simulator grants access to consumer analytics (refer 6. Consumer Analytics), which is rarely the case, you should get a glimpse of how it works, and a sense of the accuracy standards.

If not, then you need to test it under various scenarios. You may also seek validation from marketing veterans who have in-depth knowledge of the marketplace, and extensive experience in analysing market intelligence. You should likewise consider the competencies of the developer of the simulator.

2. The Developer’s Competencies

Developing authentic simulators requires an in-depth understanding of the forces that impact the marketplace and extensive knowledge of the market models used to analyse, interpret, and forecast market responses. Because marketplaces are multifaceted, developing an authentic simulator is a highly complex task. So, chances are that truly authentic simulators are developed by those who focus on the industry sector that they specialize in.

Development should be guided by seasoned practitioners, i.e., veterans who analyse real market data on a regular basis. They need to have a clear sense of how the marketplace responds to marketing stimuli for the industry sector being simulated.

This contrasts with organizations that offer a suite of so-called simulators. More often than not, the development is guided by teams that lack the required industry expertise, relying mainly on theoretical knowledge. The outcome is simulators that seem logical but fail to replicate real market complexities. They lack real market sense.

3. Use of well-established Market Models adopted by practitioners

At Nielsen, while regionally heading client servicing, I learned that some of the top consumer-facing firms spent close to a billion USD globally every year on marketing research. They do so because marketers base their business decisions on the accurate market intelligence and insights procured from their trusted research and analytics partners.

Analytics firms like Nielsen, Millward Brown (now Kantar), and many others, along with market-leading manufacturers like P&G, Coca-Cola, Kraft, and Unilever, are at the forefront of marketing science.

In the context of marketing practice, as can be gauged from industry spend levels, solutions that exist in the industry outweigh the contributions from academia. Whereas academics often stretch the boundaries of reality and explore possibilities, marketing analysts and researchers in the industry offer solutions that are grounded and better suited for marketing practice.

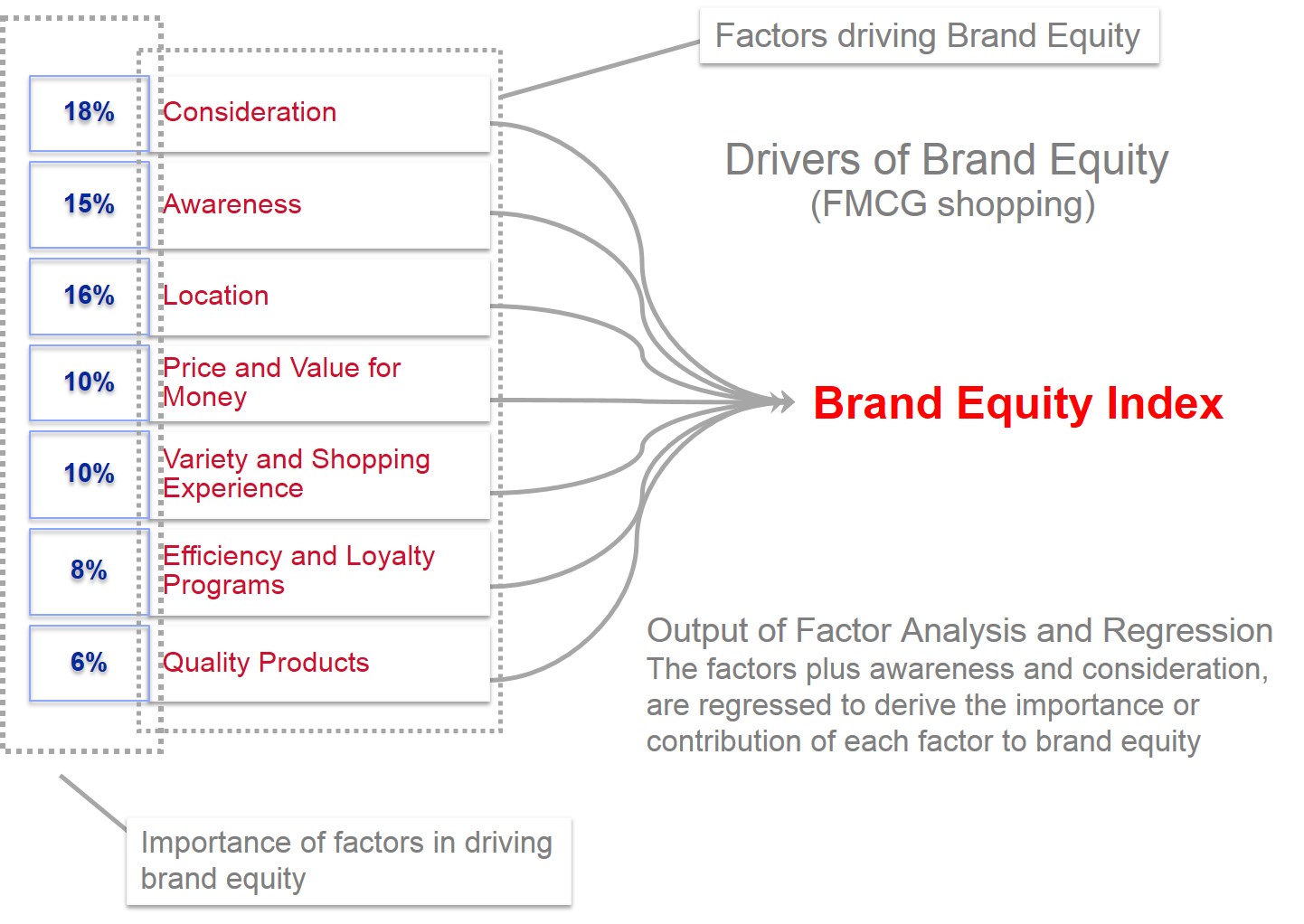

Exhibit 2 The brand equity model is one among a number of algorithms used for determining brand choice in the Destiny simulator.

As such, an essential requirement for marketing simulators is the use of well-established, proven industry marketing models. To gain industry-wide acceptance, these models should be based on research concepts that are widely deployed in modern-day marketing practice. They should impart an understanding of what drives store choice and brand choice, what triggers brand/store switching, how advertising channels brands/banners into consumer repertoires, and how consumers respond to different types of promotions and incentives.

4. Disaggregate Simulation

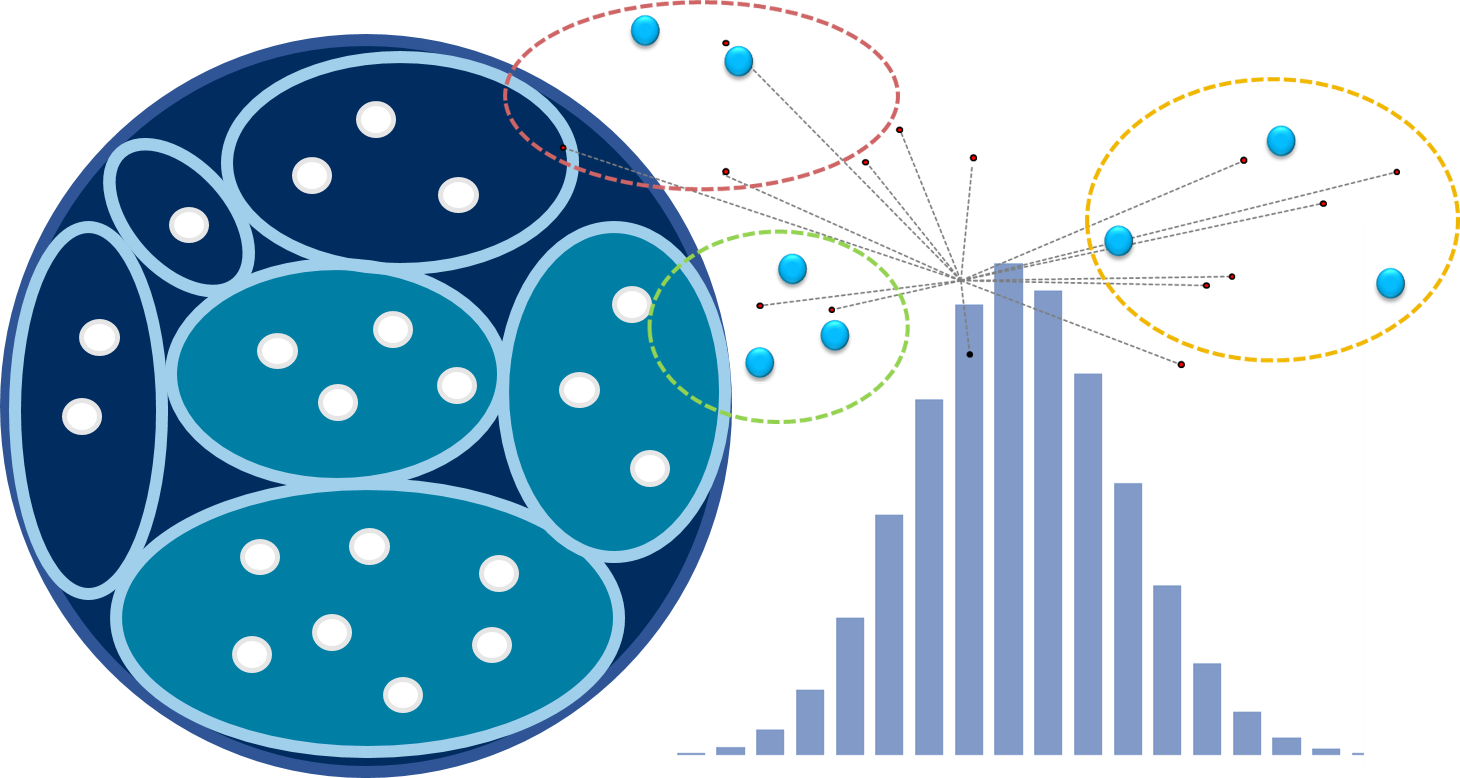

Exhibit 3 Marketing simulators should work with disaggregate data, i.e., virtual households or individuals, in order to fully capture the heterogeneous nature of consumer markets.

Real life is disaggregated. In a city, there are millions of individuals and homes, and thousands of retail outlets, both online and offline. Outcomes are probability-based. The normal distribution is said to represent an elementary “truth about the general nature of reality.”

A simulator’s structure and its data’s granularity must therefore be disaggregated. They ought to run on thousands of virtual households or individuals to fully capture the heterogeneous nature of consumer markets. Where these households shop and what brands they purchase over a period of time is simulated based on marketing models that predict consumers’ response to the elements of the marketing mix.

The behaviours of these individual buyers, who differ in terms of their preferences and past purchasing behaviours, are simulated and then projected to reflect the outcome for the whole population.

The issue with disaggregate simulators is that they are highly resource intensive. When I worked with such techniques at Unilever in the early nineteen nineties, I would leave my personal computer on throughout the night, and it might still be running the next morning. And when I first started using simulators for teaching purposes about twenty five years back, the simulation took about half an hour to run, far from ideal if you are conducting an exercise in real-time, and participants are waiting for the results.

Fortunately, today, on relatively basic servers, simulating a few thousand households takes no more than a minute or two.

Since the disaggregate structure complicates software development and slows down the simulator, very few marketing simulators are disaggregate simulators. This is regrettable because aggregate simulators present an overly simplified view of the marketplace. You tend to see artificial swings and patterns in behaviour that seasoned marketers find hard to accept.

The way to distinguish a disaggregate simulator is through the data, which is maintained at a disaggregate level. Unlike aggregate simulators, disaggregate simulators can run consumer analytic analysis that examines buying behaviours to determine usage patterns, behavioural loyalty, and switching patterns, and perform predictive analytics such as forecasting market share.

These consumer analytics techniques relate primarily to products that are frequently purchased, such as fast-moving consumer goods or consumer packaged goods.

The other key difference is that for probability-based simulators, the array of store choice and brand choice models includes elements of randomness. Every time the simulation is run, the results will differ, even with the same parameters (decisions). This differs from the deterministic models used by aggregate simulators that do not include elements of randomness. Every time you run a deterministic model with the same initial conditions, you will get the same results.

5. Are the metrics/dashboards for Real?

If not, then the simulator serves no practical purpose. What use is information that is never available in real life? Why equip a surgeon or a marketer with tools that do not exist?

It is important not only that the metrics are the same as those that the marketer use in real life, they should also be presented in a manner that professionals are accustomed to.

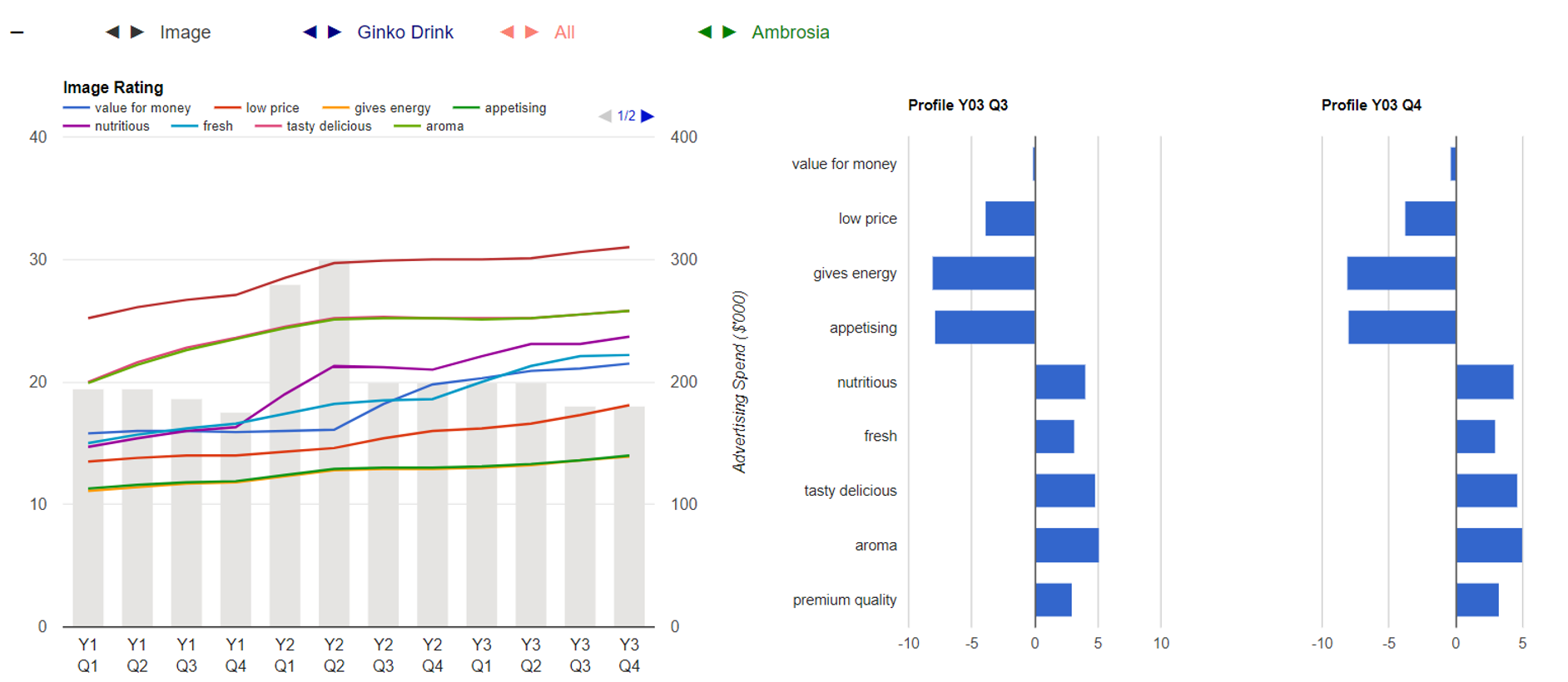

Exhibit 4 Dashboard depicting image profile. (Source Destiny simulator).

The above exhibit depicts one of the nine market dashboards that comprise the Destiny simulator’s suite of reports. As may be the case for other simulators, Destiny’s data visualization platform is superior to the platforms that exist in the industry. This is because, due to the existence of multiple analytics and research agencies, real market data often exist in silos.

That said, the industry norms must not be compromised, and the definition of metrics should remain consistent with marketing practice, as is the case with the Destiny simulator.

6. Consumer Analytics

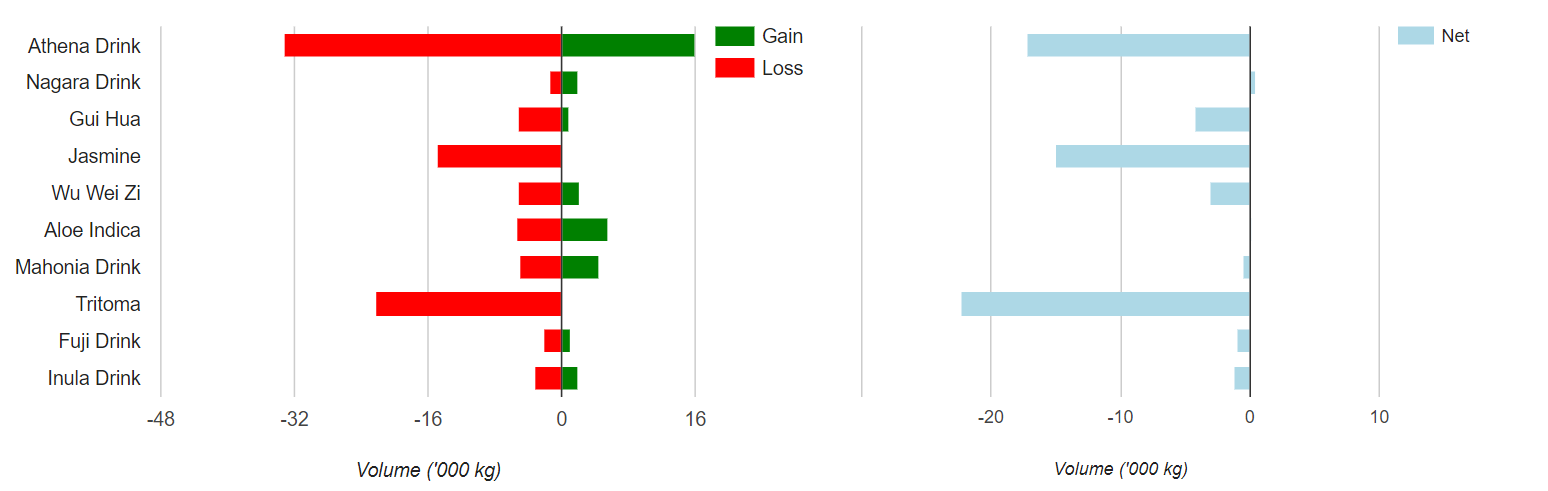

Exhibit 5 The gain-loss analysis (brand switching analysis) shown here can be performed with disaggregate data. (Source Destiny simulator)

Consumer analysts and marketers from the major consumer marketing firms tend to be proficient in the use of consumer analytics. So, if that is your target market, you should consider simulators that can switch on analysis such as gain-loss (Exhibit 5), overlap, buyer basket, behavioural brand loyalty, trial and repeat and so on. Consumer analytics modules also have the facility to perform predictive analytics such as forecasting market share based on trial and repeat purchasing (RBR, repeat buying rate) behaviours.

For the reasons mentioned under the section disaggregate simulators, very few marketing simulators are likely to offer consumer analytics. But if they do, it is a positive indicator of authenticity.

The disaggregate data analysis obtained from the consumer analytics module is highly diagnostic. The facility allows users to cut open the black box and examine the inner details. You get a glimpse of how it works, a sense of the accuracy standards, and an appreciation of the level of sophistication.

If you are using a simulator with consumer analytics, I would advise you to switch the module on towards the second half of the exercise so that the learning curve is not too steep at the start.

For more information on consumer analytics, refer the chapter Consumer Panels and Consumer Analytics on MarketingMind.

7. The modules

A simulator should comprise of a host of modules or platforms that serve the diverse needs of the various stake holders that use the device. These modules which are listed below should make it easy for users to navigate.

- Simulator,

- Market dashboards to visualize the market outcomes of the simulation,

- P&L to depict the financial outcomes,

- Consumer analytics platform for data mining and disaggregate analysis,

- User-friendly decision templates with user aids,

- Contractual agreements (where relevant) – online platforms that allow trade partners to negotiate trading terms,

- Handbook that not only guides users on how to use the modules, but also advises them on how to make good decisions,

- ‘How it works’ technical guide outlining the theoretical foundation.

8. Online Simulators

In the early days, simulators relied on spreadsheets for inputting decisions and displaying dashboards, pen and paper for chalking out contracts, and thumb drives for transporting data. Participants had to be physically present.

All that has changed. Everything should now be online so that teams can work concurrently from different locations across the globe.

Not only is this extraordinarily more efficient, it reduces the cost and inconvenience of travel. It also allows the exercise to be extended beyond days, stretching into weeks or months.

It is ideal too at times when restrictions such as during covid, are in place.

9. Use of Metadata for Assessment

“Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.” — Winston Churchill

Instructors must appreciate that a simulation-based training programme is not about winning or losing. It is about applying and imbibing marketing concepts and processes and gaining experience. What participants learn and retain is what matters.

As is the case in real markets, the brands in the simulation are not equally well endowed. Some are inherently stronger than others. Some businesses and brands are resilient, while others are weak. Often there exist underlying forces generated over time that support some brands and keep them strong, while other brands experience downward pressures due to inherent weaknesses in their marketing mix. Evaluation should therefore take into account that the fate of brands is shaped by several pre-existing factors.

In such a scenario where simplistic cross-team comparisons do not apply, benchmarks drawn from the metadata of prior simulation runs should form the basis for assessment. A team’s performance ought to be benchmarked against previous teams that managed the same company, on key health measures.

In other words, the simulator must maintain a record of the outcome of simulations over time so that benchmarks can be drawn for key metrics. These should be measures like market share, revenue, and operating income that marketers commonly use to set KPIs in their real work lives.

The quality of negotiations, efforts in developing long-term business partnerships, and the extent to which partners leverage their complementary resources and capabilities to capitalize on marketplace opportunities should also contribute to the overall assessment.

Instructors need also to be mindful of endgame tactics. Manoeuvres where assets are milked towards the end of the simulation to boost profitability at the expense of the long-term health of the business should be penalized.

10. Limitations

Once you have chosen the right marketing simulator, do remain mindful of its limitations. Some of these are generic and cut across all simulators.

We know, for instance, that quality is key to the success of advertising, and we have heard people say, “half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is, I don't know which half.”

Simulators make assumptions, such as, for instance, that advertising consistently works (i.e., it is impactful), or that it is possible for all products to improve product quality. In reality, it takes several months to develop new enhanced products, and the quality of advertisements usually varies considerably.

Note also that good simulators provide estimates on metrics like volume and market share that, like real market research data, are affected by sample size. The randomness or variance gets exaggerated for small brands, where the effective sample size is small. These inaccuracies increase when we view data at more granular levels, such as segment or chain level, because the sample size shrinks.

I should also mention that data, particularly aggregate data, is often opaque. To quote Laurence J. Peter, “Statistics are like a bikini. What they reveal is suggestive, but what they conceal is vital.”

Consider, for instance, the P&L for a loss-leading traffic builder, i.e., a high-ranking product that draws shoppers because it is attractively priced or promoted. The P&L provides a blinkered view that suggests the brand is losing money.

The financials fail to reveal the impact of the increased traffic the product is generating. The additional shoppers are buying many other products, and the purchases of those products usually more than compensate for the loss incurred by the loss leader.

The P&L also does not reveal the impact a traffic builder may have on future sales. A well-construed strategy will result in attracting new or lapsed shoppers to the chain, and some of these shoppers will continue shopping at the chain.

Incidentally, whereas the P&L is less revealing, advanced users who are proficient in the use of consumer analytics may dive into the analytics module (if available) to assess these relatively opaque influences.

Conclusion

Having created simulators and used them for training purposes for several years, I can say without hesitation that marketing simulators are immensely beneficial for the development of marketing, retailing, sales, and trade marketing professionals. Within a relatively short time frame, participants acquire a stronger sense of the marketplace and become proficient in the use of market intelligence and financials for making business decisions. They also learn to appreciate the role of trade marketing in building marketplace equity.

For authenticity, simulators must incorporate the multifaceted nature of consumer markets. This makes them detailed and somewhat elaborate, and it takes users who are unfamiliar with market dynamics some time to get acquainted and accustomed to the simulated marketplace.

Instructors need to devote time to evaluate options and choose a simulator that is best suited for their industry. More of their time is then required in learning how to make the best use of the simulator in their training program. For the initial routes, they may need to rely on the support of the vendor for training and guidance.

The author, Ashok Charan, is the developer of the Destiny marketing simulator. He has over 26 years’ industry experience, working at companies like Unilever and Nielsen, and is currently teaching at the NUS Business School.

Related articles:

- Simulators becoming essential Training Platforms

- What they SHOULD TEACH at Business Schools

- Experiential Learning through Marketing Simulators

- Negotiation Skills Training for Retailers, Marketers, Trade Marketers and Category Managers

- Self-Learners: Experiential Learning to Adapt to the New Age of Marketing

Destiny: Consumer Marketing Simulator

Previous Next

Use the Search Bar to find content on MarketingMind.

Contact | Privacy Statement | Disclaimer: Opinions and views expressed on www.ashokcharan.com are the author’s personal views, and do not represent the official views of the National University of Singapore (NUS) or the NUS Business School | © Copyright 2013-2026 www.ashokcharan.com. All Rights Reserved.