“If you’re not thinking segments, you’re not thinking.” —

Theodore Levitt.

The development of your

brand’s marketing strategy, in a nutshell, entails choosing which segments to

target, differentiating the brand to appeal to the segments, and positioning it

distinctly in the minds of target consumers.

Market segmentation is typically defined as the

process of partitioning a market into groups of consumers with distinct needs

and preferences. For many categories it might be better to describe it

as the process of partitioning a market into groups of consumers’

need-states, reflecting distinct needs, preferences and circumstances. The

same consumer often falls into multiple segments, her preferences varying

according to her need-states.

Consumer Needs

What exactly constitutes a

need? What are the factors that influence consumer buying behaviour? This by

itself is big topic, one that is covered in brief, in most marketing management

texts. Kotler (2009) describes four underlying influences — cultural, social,

personal and psychological. An individual’s social class, social network, family, income class, occupation, lifestyle, age, generational cohort, her level

on Maslow’s needs hierarchy … all these factors and more, shape her beliefs and

attitudes. These beliefs and attitudes, coupled with her mood, emotion or

circumstance, drive her motivations and buying behaviour, at any moment in

time.

The gamut of influences, moods, emotions, and

circumstances etc. that drive buying behaviour make segmentation seem a

daunting exercise. Yet while the possibilities seem endless all underlying

influences do not necessarily shape people’s beliefs and attitudes in such a

way that it changes their buying behaviour. Depending on the nature of the

product category, some influences are more important than others.

Mental Heuristics

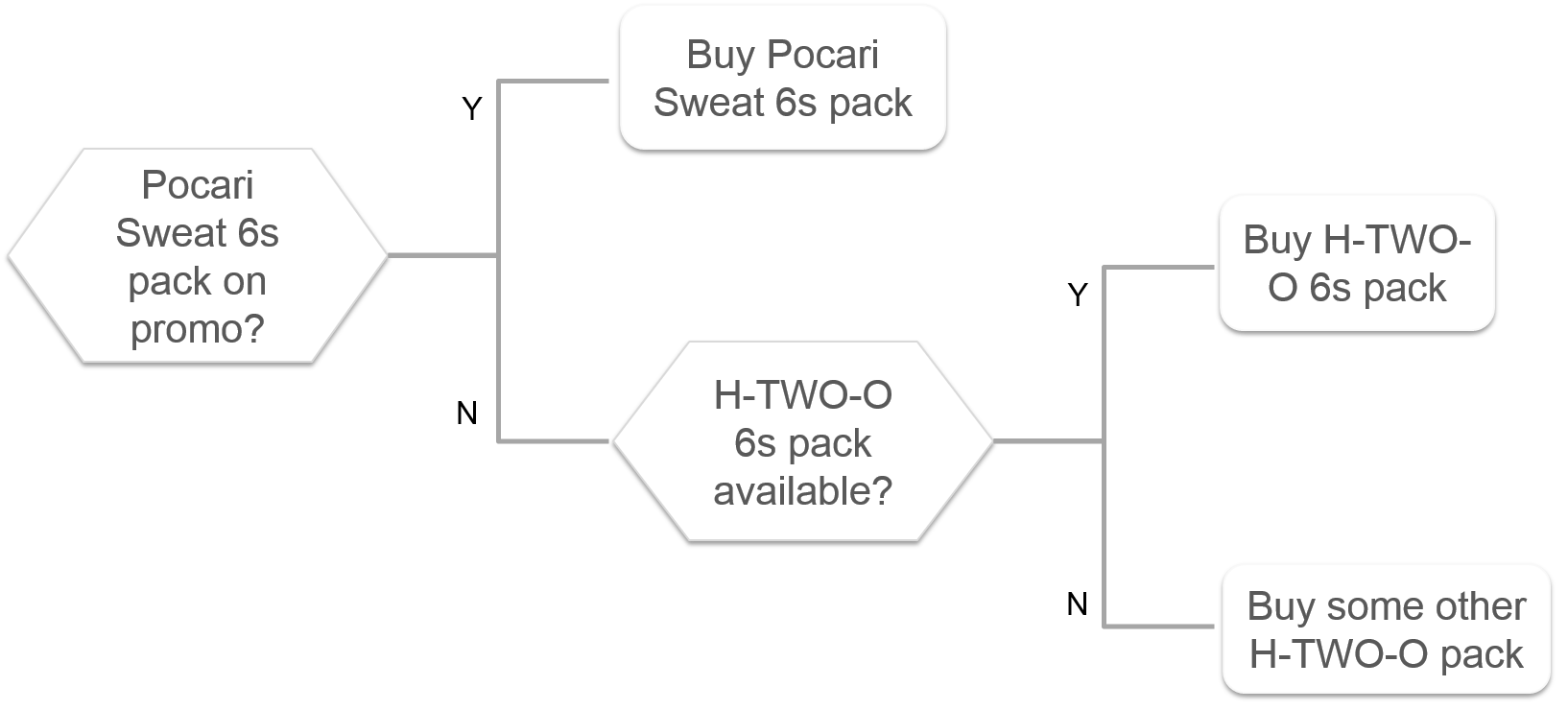

Exhibit 3.1 A consumer’s decision rules for buying isotonic drinks.

Confronted with a whirlwind

of information and hundreds of choices in each category, consumers develop

simple decision rules or mental heuristics. For low budget purchasing decisions

as in FMCG, these rules can be fairly straightforward.

For instance, “I always buy Lipton Yellow Label

tea”. Or for instance the set of rules depicted in Exhibit 3.1, where the

consumer prefers Pocari Sweat when it is on promotion, otherwise he buys

H-TWO-O. Most brand choice decisions are based on similar, simple decision

rules. It saves time and energy.

Rules make shopping behaviour habitual in nature;

more often than not a consumer purchases the same set of her usual FMCG brands.

Yet there are moments that may trigger a change. Whether it is disappointment

with her existing brand, the launch of a new product, the incidence of a

stockout, an attractive promotional offer for a competing product or a host of

other factors, from time to time she is induced to break out of her habits and

try something different. These moments represent the window of opportunity that

competing brands seek to exploit.

For segmentation purposes, marketers need to

understand the heuristics that dictate consumers’ buying habits. What sets of

rules apply for each of the different need-states? How do they evolve? What

factors influence the formation of the rules? Are the rules backed by an

emotional commitment to the brand? What motivations trigger changes to the

rules?

The diversity of rules reflects the heterogeneous

nature of markets. Marketers can benefit from an understanding of how

underlying cultural, social, personal and psychological factors influence the

individual’s different need-states, and how they in turn lead to the formation

of rules.

Forms of Segmentation

Segmentation should be based on

consumer needs. The term however is broadly used to describe various ways of

classifying consumers or products. For example, take demographic segments. It

assumes that the needs of consumers vary from one demographic group to another,

which might be true, though it may not be the ideal or the best way to segment

the market.

The objectives of a segmentation exercise also

vary. If the exercise pertains to a specific marketing mix decision, the

segments are crafted in the context of that element of the mix. For example, a

marketer interested in crafting consumer price segments, would use appropriate

variables and methods for this purpose.

There are a variety of methods and numerous

techniques to segmenting markets. Broadly speaking, these methods may be

classified as a priori, where the segments are determined in advance; or

post hoc where analytic techniques are employed to carve segments out

from the data.