PREVIEW

Copyright © 2017 by Ashok Charan

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the author, ashok.charan@gmail.com.

National Library, Singapore Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library, Singapore.

ISBN

A2017041100001

First Edition

Printed in Singapore.

www.ashokcharan.com

Preface

Marketers often build cyber assets, such as websites, Facebook pages, and YouTube brand channels, without giving much thought to the overall strategy or execution. The outcome is a collection of disconnected properties that diffuse and disorient their brand and confuse customers.

To avoid these pitfalls, it is crucially important to develop a cohesive strategy that integrates all offline and online brand assets. This strategy ensures that your brand’s communication and imagery remain intact as customers move across different media platforms, while each channel plays a distinct and coordinated role. This book aims to help you achieve these outcomes by providing a clear understanding of the building blocks of digital marketing and equipping you with the tools, techniques, and knowledge to develop cohesive market strategies and execute effective digital marketing campaigns.

This practitioner’s guide complements the Digital Marketing Workshop, where participants benefit from hands-on training that allows them to put into practice what they have learned.

Ordinary people empowered with the social media are interacting and collaborating with unprecedented speed, reach and effectiveness. This has had a profound impact on society, reshaping political, economic, and cultural landscapes worldwide. Marketers must adapt to these changes and embrace digital marketing with a multi-pronged strategy to attract, convert, and retain customers. On the web, the focus shifts from “buying” attention and pushing products to providing useful, relevant, and interesting information to draw customers in.

Anchored in the age of social media, this book serves as a practitioner’s guide to digital marketing. The first chapter, New Media, explores the impact of new media on the social, political, and marketing landscape. It imparts key lessons for marketers and outlines the new rules and perspectives, leaving readers with a clear understanding of how they must adapt to succeed in the digital age.

The subsequent chapter, Digital Marketing, covers a wide range of topics related to digital tools, techniques, processes, as well as the opportunities and challenges of digital marketing. A series of chapters on social media delve into the core differences between popular platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn, offering best practices to adopt for each platform.

The chapter on Search Engine Optimization (SEO) explains on-page and off-page optimization techniques to help readers increase inbound traffic and channel it through the digital marketing funnel.

The chapter on Web Analytics delves into the processes that constitute a web analytics system, emphasizing the use of platforms like Google Analytics to assess the effectiveness of digital marketing in attracting and converting prospects.

Search Advertising, another chapter, provides insights into advertising on search engines to attract prospects and lead them through the digital marketing funnel. It covers topics such as the Google auction, keyword strategies, and practices to enhance the effectiveness of search advertising.

The final chapter, Digital Execution, serves as a comprehensive guide to developing and executing digital marketing plans. The book also includes coverage of the use and application of popular digital analytics platforms such as Google Search Console, Google Analytics and Google Ads.

This guide is written with the practitioner in mind, offering a thorough understanding of digital marketing and serving as a valuable resource in the field. It will guide you as you develop and execute digital marketing strategies.

Author

Ashok Charan

Publisher/Developer — MarketingMind, Destiny Marketing Simulator.

Author — The Marketing Analytics Practitioner’s Guide.

Academics — National University of Singapore, Business School.

www.ashokcharan.com, ashok.charan@gmail.com.

Ashok is a renowned expert in the fields of marketing analytics and digital marketing. He is the author of several books on these topics, the creator of the Destiny marketing simulator, and the developer of various tools and solutions for practitioners, such as MarketingMind, an eGuide for consumer analysts and marketing professionals.

A marketing veteran, he has over 25 years of industry experience in general management, corporate planning, business development, market research and marketing. Prior to joining academia full-time, Ashok worked with Unilever and Nielsen where he assumed a number of leadership roles including Managing Director for Singapore, and Regional Area Client Director for the Asia Pacific region. His experience spans both business and consumer marketing, and he continues to consult in the areas of marketing analytics and research, business intelligence platforms and data integration.

Ashok is an engineering graduate from the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, and a post-graduate in business management (PGDM) from the Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta.

Destiny, Marketing Simulator

Destiny simulates the purchasing journey cycles of households within food and personal care categories, using market models that predict consumers’ responses to the elements of the marketing mix.

The simulator’s suite of visualization dashboards supports a wide range of metrics so that participants can easily analyse their markets. Destiny also supports a dazzling array of consumer analytics techniques that permit participants to mine, filter and drill into continuous, shopper level transactions.

Destiny is used with The Marketing Analytics Practitioner’s Guide in experiential learning modules for executive education and Executive MBA, and for graduate and under-graduate courses in marketing analytics and strategic marketing.

Contents

Spread of Misinformation — Fake News

Levelling the Marketing Playing Field

Inbound and Outbound Marketing

New World: Digital Transformation — Real Estate

Consumer Trends — Media Consumption

Online Video Distribution Trends

Engaging with Consumers in Cyberspace

Word of Mouth and Brand Meaning Management

Buzz (word-of-mouth) Marketing

Growth of Advertising on the Internet

Viral Advertising — Challenge of Reaching the Masses

Organic Marketing — Best Practices

Limitation of Instagram Desktop

Organic Reach — Instagram Algorithm

LinkedIn Marketing for Businesses

LinkedIn Analytics — Posts and Articles

What constitutes a View on Posts?

LinkedIn Marketing — Factors to Consider

Chapter 8: Search Engine Optimization

Search Engine Optimization — Overview

Landing Pages — Approach to SEO

Targeting Keywords and Phrases

Category, Brand and Competitor Keyword

Google’s Ad Auction — How it Works?

Google Ads — Advertising Architecture

Google Ads — Ad Format & Anatomy

Long Tail and Short Tail Keywords

Category, Brand and Competitor Keyword

Keyword Ideas to Select Keywords

Keyword Search Volume and Conversions Forecast

Execution: Practices to Improve Effectiveness of Search Advertising

How Proxy Servers bypass Filters and Censorship

Data Collection — Page Tagging (JavaScript)

Drawbacks of using Cookies for Tracking Users

Data Collection — Authentication Systems

Time Duration, Pages/Session and Engagement

Conversion and Conversion Path

Markov Chain — Probabilistic Data-Driven Attribution

Global Positioning System (GPS)

Industry Benchmarks and Competitive Intelligence

A/B testing and Google Optimize

Chapter 11 Digital — Execution

Languages that enable the World Wide Web

Content Management System (CMS)

Conversion — Digital Marketing Funnel

Monitor Performance – Review Progress

References

Preview — Snippets from the eGuide

Chapter 2 — Digital Marketing — Preview

What Works Online

A fundamental shift in mindsets must occur for marketers to succeed in digital marketing. On the web, they need a pull strategy to attract customers by serving useful, relevant and interesting information. This contrasts with conventional media which involves different forms of "buying" attention to push products to customers.

A pull strategy is even more important for products that consumers do not usually seek information about on the net. Take shampoo for instance — consumers do not usually go to the net to decide what shampoo to buy, yet they do discuss their hair issues there. According to NM Incite’s white paper (December 2012) there were 2.3 million messages on hair care on social media in the U.S., for the first 6 months of 2012, and only 4% of these pertained to specific hair care brands. Top google searches in hair care, depending on country, usually cover topics such as hairstyles, hair fall, haircuts, hair colour, shampoo, long and short hair and hair salon.

When initially launched in June 2006, Hindustan Unilever’s Sunsilkgangofgirls.com exemplified the pull strategy. Proclaimed as India’s first “online all-girl community” the site provided social networking space and consumer generated content features such as blogs and communities (gangs). Content-wise it focussed on hair, beauty and fashion, and prominently featured hair care experts.

Promoted through a media blitz, the site attracted a high level of interest from its target group, garnered a large base of registered users and “gangs”, reached almost 200 million hits and was attracting an average of 12–13 million page views per month.

The website evolved over time and is now more brand-centric (see Exhibit 2.1) than it used to be. Linked with Sunsilk’s Facebook brand page and Twitter, the website now places greater emphasis on networking through these platforms as opposed to developing their own — i.e., you can no longer form a “gang” on the site. Well aligned with its identity, it continues to serve the information that target consumers are seeking, offering tips from hair experts on hair care, hair trends and fashion, in addition to information about the Sunsilk brand.

Though the site has now been removed, P&G’s BeingGirl.com ((Exhibit 2.2), which offered advice on puberty and periods for teenage girls, in a teen-friendly manner, was another apt example of a helpful and informative site. According to Velvet Gogol Bennett, P&G’s North America’s feminine care external relations manager: “It’s a safe place where they can go for information about changes they are experiencing but are too embarrassed to discuss.”

Some criticism arose due to accusations of “exploiting” teenage girls, which could have been avoided if the company was more selective on their choice of content. P&G’s current feminine hygiene websites such as Always.com, remain very informative and helpful. No longer purely teen-centric, the sites use personalization to filter content according to the user’s age profile.

Pampers.com, which offers baby and parenting advice, is yet another example of a site that attracts consumers by providing the information that they are seeking. The site is also a good example of the use of personalization in crafting a website. When a mother visits www.pampers.com, the content on the website is filtered and displayed according to her baby’s age group.

Exhibit 2.3 Sugarpova was launched with a budget of US$500,000, using primarily new media.

As mentioned earlier, the internet is a great leveller. A new or unheard of brand, could gain awareness, and build relationships with consumers without having to spend the kind of money that is required in conventional advertising. Sugarpova is one such example.

At an initial investment of only US$500,000, Maria Sharapova made effective use of the new media to market Sugarpova, a new candy line. On 20 August 2012, armed with her star power, and 10.5 million Facebook fans and 400,000 followers on Twitter, she launched the premium candies without mainstream advertising.

It was candy veteran Jeff Rubin who conceived of the product concept and coined the name Sugarpova. The candies are available in a variety of flavours which come with labels such as "Flirty", "Smitten Sour", "Sassy", and "Splashy". They may be bought online on Sugarpova’s website (Exhibit 2.3) or at select outlets in a number of countries across the globe.

About a year after the launch of Sugarpova candy, Maria Sharapova introduced a range of clothing and accessories under the same label. Later in 2014 she launched "Speedy", a yoghurt gummy that comes in the shape of the iconic Porsche 911. And, more recently, in 2016, partnering Baron Chocolatier, she introduced the “chocolate collection”, premium chocolate bars launched in four flavours.

Sugarpova carved out a niche with global sales of US $6 million in 2013. Since then, according to the company’s sources, year-on-year sales continued to grow double-digit, driven primarily through digital marketing.

Exhibit 2.4 Chobani features extensively in blogs such as sweetdealin and mealsandmovesblog where this CHOmobile visual has been sourced from.

Unlike Maria Sugarpova, Hamdi Ulukaya, the founder of Chobani, did not have a large fan base on social media, when he first ventured into the yogurt business. Hailing from a dairy-farming family from Turkey, he came to the U.S. in 1994 to study. Eleven years later, his decision to purchase a defunct yogurt factory from Kraft Foods, was based primarily on his conviction that consumers would prefer the thick, strained yogurt which he grew up with in Turkey, as opposed to the sugary, watery and “artificial” varieties that were available in the market in 2005.

Starting with just 5 employees, and lacking a big marketing budget, Ulukaya made use of the internet and social media to reach out to a large base of bloggers, and connect with consumers on Facebook and Twitter. The online buzz that these initiatives generated was instrumental to the success of the brand during its infancy.

Sales accelerated in 2010 spurred by the CHOmobile (Exhibit 2.4), a sampling truck, which handed out free cups of Chobani yogurt at festive and family-friendly events all over the U.S.

Chobani grew into a $1 billion empire within five years of launch, leading the U.S. yogurt by 2011, and Greek yogurt’s market share in the U.S. surged from less than 1% in 2007 to more than 50% in 2013.

Since 2013 Chobani’s yogurt sales have tapered and started to decline, and the company has expanded its product range to include Chobani Mezé yogurt-based dips, yogurt drinks, and foods for toddlers containing ingredients such as Omega-3 DHA and live and active cultures, in addition to yogurt and fruits.

To a great extent Chobani’s success may be attributed to its highly effective social media strategy. According to Ulukaya, “We knew we had a great tasting, good-for-you product, now we just needed to get people to try it. Sampling and word-of-mouth was huge for us, especially at the start, as we had no money for traditional marketing or advertising.” And so, from the onset, consumer-driven social media marketing was the preferred approach.

Chobani’s website is littered with stimulating recipes and photos that evoke excitement and interest. As mentioned earlier, the company reached out extensively to bloggers, and it is heavily engaged and active in Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Pinterest and Instagram, where it strive to create an atmosphere that is “warm and quirky, engaging and inviting”. Chobani also uses the foursquare search-and-discovery mobile app to promote tours and events, and to help consumers locate CHOmobiles.

As of October 2016, Chobani has over 1.3M fans on Facebook, which takes it well ahead of other yogurt brands. Their YouTube channel has 16 million views since its inception in 2009. And according to company sources, they garnered over 10 billion earned media impressions, during 2013.

A good social listener, Chobani gained valuable insights that shaped the development of new flavours and new products. One of their bestselling flavours, black cherry, came about from a consumer request.

Always responsive to consumers, Chobani exhibits exemplary social accountability, and effectively manages work-of-mouth. Company sources claim they respond to every consumer inquiry, and as can be seen from their Facebook page, they are well engaged.

In 2012, when there was a voluntary recall for some of their products due to mould contamination, the company responded by sending personalized letters from CEO Ulukaya. According to Chief Marketing Officer Peter McGuinness, “He wanted to write a personal letter to each of the 150,000 people that had an issue with our product because he takes it very personally and very seriously, and he wanted to thank them for ... sticking with us and standing by us.” Taking this a step further, Chobani sent trucks across the country to celebrate with their consumers by throwing yogurt parties. Giving away free products was their way of rewarding fans for their loyalty.

Chobani’s brand identity centres on goodness, nature and health, and this is reflected in their taglines “Nothing but Good”, “Simple, Pure food”, “You Can Only Be Great if You’re Full of Goodness” and “No bad stuff”. The brand’s image and identity is interwoven with consistency across the social and conventional media.

One of the interesting facets of Chobani’s media strategy, is the emphasis on the values, lifestyles and causes. Their communication is not always product or brand centric, and, according to company sources, web metrics reveal that consumer engagement ranked highest for postings about their “brand’s values and personality but not directly about yogurt”.

This may partly be the outcome of the company’s humble beginnings. The Hamdi Ulukaya story inspires people, and it has helped associate the Chobani brand with a dose of aspiration and the spirit of achievement — “Our story proves that the American dream is alive and well”.

The company’s willingness to take a stance on social matters is reflected in the “To Love This Life is to Live Naturally” campaign which showcases LGBT acceptance, as also to their opposition to Russia’s anti-LGBT law, and their defence of LGBT athletes in the Sochi Olympics. It supports social causes through its participation in community activities, and by donating a proportion of its post-tax profits to charity.

Chobani is no longer a small company and their marketing budget has grown substantially as can be gauged from their sponsorship of successive Olympics and Paralympic Games. These sponsorships where athletes have free access to an array of Chobani product, are among some of the company’s greatest marketing feats. The company’s presence and actions at these events has spawned a wealth of stories that have helped to feed the interest and excitement for Chobani in social media.

Chapter 3 — Digital - Execution — Preview

Nurturing Leads

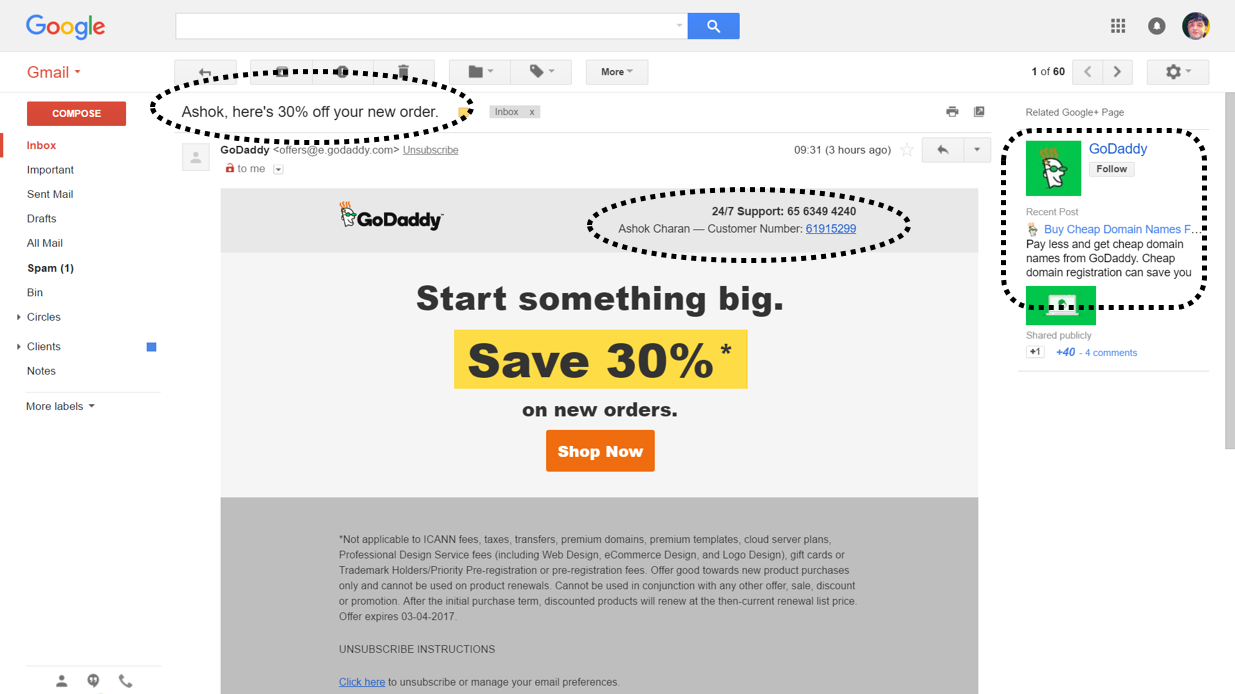

Exhibit 3.10 GoDaddy targets existing customers with promotional offers on new orders.

Nurturing is the process of developing relationships with your prospects by engaging with them in ways that benefit the prospects. It focuses efforts on listening to their needs, and offering well-intended advice, information and solutions to address their needs.

Nurturing takes place at all stages of the marketing funnel, at every step of the prospect’s journey. The processes and tactics commonly employed include:

- Follow-up leads by email, webinar, web chat, sales call and so on. Exhibit 3.10 depicts an example where GoDaddy is targeting an existing customer through an email with a promotional offer for new orders.

- Retarget ads to remain in prospects’ minds.

- CRM (customer relationship management) practices to manage, analyse, engage and build relationships.

- eCommerce to facilitate the sales process.

Nurturing that engenders trust is far more effective in building relationships. Since you cannot win prospects and earn their trust by bugging them, it is important that intrusive approaches such as emails are directed to those who opt-in, or at least, have the provision to opt-out. For instance, the email offer by GoDaddy shown in Exhibit 3.10 provides unsubscribe instructions at the end of the message.

To get prospects to opt-in, you need to create fresh opt-in opportunities. This demands constant efforts on your part to craft messages and develop materials that are beneficial to your prospects.

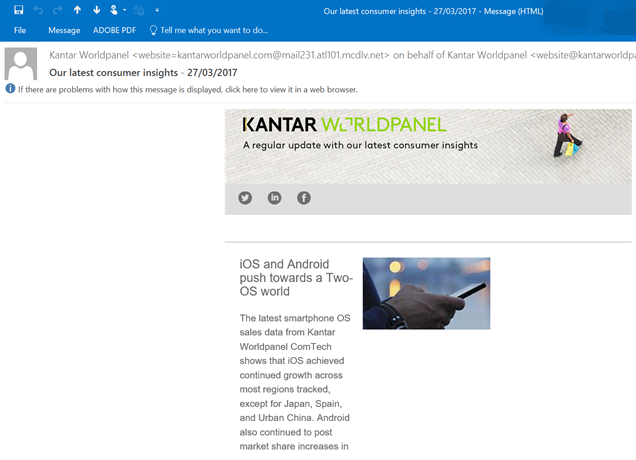

Exhibit 3.11 Kantar Worldpanel’s emails sharing their latest consumer insights help to raise the top-of-mind presence of the vendor in the minds of prospective customers.

‘Pot sweeteners’ can be used effectively to build relationships. These are items of value to prospect, but which do not cost much to produce.

For example, as shown in the email in Exhibit 3.11, the Kantar Worldpanel shares research insights with prospects, in an effort to strengthen relationships and remain top-of-mind.

With emails, it helps if you can develop a personal touch. Personalization, in part, is a function of knowing your prospect and sending the right messages. It is also important that real people are sending out emails, as opposed to “this is a computer generated message”.

Emails campaigns should be evaluated primarily on the basis of behavioural aspects such as the frequency of visiting website, the items downloaded and the pages visited.

It is important to keep your end goal in mind, particularly when nurturing prospects, and that you ensure your messages are aligned with the goals.

Chapter 4 — How Advertising Works — Preview

Emotion in Advertising

A few years back, a video depicting an ordinary family enacting a driving accident in their sitting room became an internet sensation. No words were uttered in this slow motion 88-second clip that left close to 20 million viewers with a moving reminder to wear their seat belts.

The campaign by The Sussex Safer Roads Partnership taps into our emotions to stimulate and arouse attention (see Exhibit 4.7). The intensity of the emotional charge leaves images and feelings that penetrate our long term memory. Metaphors and symbols exalt the seat belt. The depiction of ordinary folk in an ordinary home, combined with the simplicity of the plot, make viewers relate with ease.

As humans we experience a wide range of emotions that affect our mood, disposition and motivation. According to David Meyers, emotions fundamentally involve “physiological arousal, expressive behaviours, and conscious experience”. They could be basic, such as happiness, security and love; or social, such as success, pride, guilt or envy.

Advertising taps these diverse emotions to penetrate our memory associating brands with positive or negative emotional states. The embrace life ad for instance, taps into feelings of love, tenderness, caring, fear, anxiety, shock and relief. The Liril girl advertisement (Exhibit 4.0) evokes the sense of freedom, hedonism and pleasure. Some advertisements reflect ecstasy and euphoria. Others dwell on fear or sorrow. Historical advertisements of Bajaj (“Hamara Bajaj”), the Indian scooter brand, and the Australian icon, Vegemite (“He’s doing his bit for his Dad …” [wartime ad]), tap into viewers’ sense of national pride.

By infusing deep feelings, these advertisements build emotional bonds that greatly increase consumers’ affinity towards the brand. It is a form of classical conditioning; the brand starts to represent those moods, feeling or emotions that it is associated with through advertising.

Chapter 5 — Advertising Analytics — Preview

Case Example (disguised) — Molly Low-Fat Hi-Calcium

Exhibit 5.9 Telepic of Molly LFHC’s advertisement. This tactical campaign is saying that Molly LFHC is fresh milk, whereas Holly HL is recombined milk.

Depending on the way it is treated, milk found in supermarkets can broadly be categorized as UHT (ultra-heat treated), pasteurized or recombined.

Ultra-heat treatment sterilizes the milk by heating it above 135 °C (275 °F) — the temperature required to kill spores in milk — for 1 to 2 seconds. However, due the high temperature, the milk loses some nutritional value.

Pasteurized milk, also referred to as fresh milk, is heated at relatively lower temperatures and for longer periods. Unlike sterilization, pasteurization does not kill all microorganisms in the food. It reduces the number of viable pathogens so they are unlikely to cause disease.

Recombined milk is obtained by adding water to skim milk powder, and adding milk fat separately such that the desired fat content is achieved. Recombined milk does not taste as good as fresh milk, and it has slightly lesser nutritional value. It is one of the preferred options in territories where there are no dairy farms, and where milk is imported from long distances.

This case example pertains to Molly low-fat high-calcium (Molly LFHC), a variant of Molly (not real name), a major liquid milk brand. When Molly LFHC was launched, a tactical advertising campaign was aired on a number of online platforms and on TV to raise awareness of the low-fat high-calcium variant, and to communicate that it was fresh and natural, unlike the leading brand, Holly HL, which was recombined milk.

The desired consumer response from the commercial was to create the perception that Molly LFHC was superior (fresh, natural) to Holly HL (recombined), and to trigger consumers to switch from Holly HL to Molly LFHC. Molly LFHC could gain substantially if it succeeded in cannibalizing Holly HL, which had 40% share of market volume.

The telepic of this commercial is shown in Exhibit 5.9. On TV it was aired over a 3-week, 420 GRP burst.

The online ad generated only a meagre 220 views, and no “likes” or “dislikes”. Holly’s online commercial, on the other hand, had achieved about 15,500 views, and triggered 15 “likes”.

Note that for a mass market product, this level of engagement is not significant, even for a relatively small geographical territory. To generate higher reach and frequency, these brands needed to rely on conventional television advertising.

A research study was conducted to assess whether the advertisement was achieving its desired objectives. The key findings from this study are portrayed in exhibits 5.10 to 5.17.

Findings and Conclusions

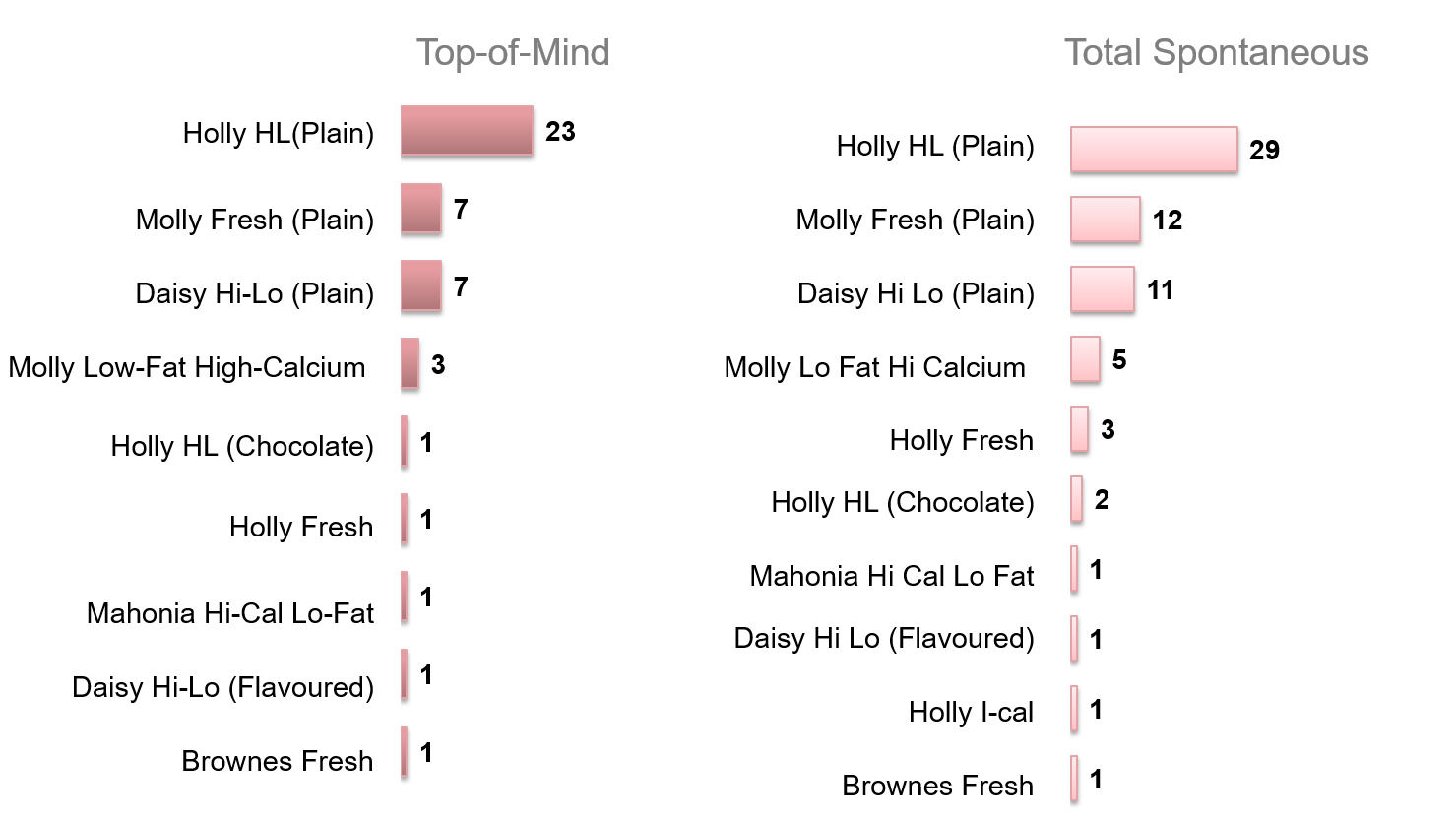

As can be seen from Exhibit 5.10, the campaign failed to generate salience. Advertising awareness for Molly Low-Fat High-Calcium was only 3% top of mind, and 5% spontaneous.

The most likely reasons for a campaign to fail to generate salience are:

- Low GRPs. This was not the case for Molly LFHC.

- Weak brand recognition. Viewers are unable to recognize the brand that is advertised.

- Lack of involvement. The advertisement lacks creativity and is unable to generate interest, in which case viewers are unlikely to remember it.

Assessment of brand recognition was based on the commercial’s telepic (Exhibit 5.9) which is presented unbranded to respondents, i.e., the brand name and logo is removed from all the frames comprising the telepic.

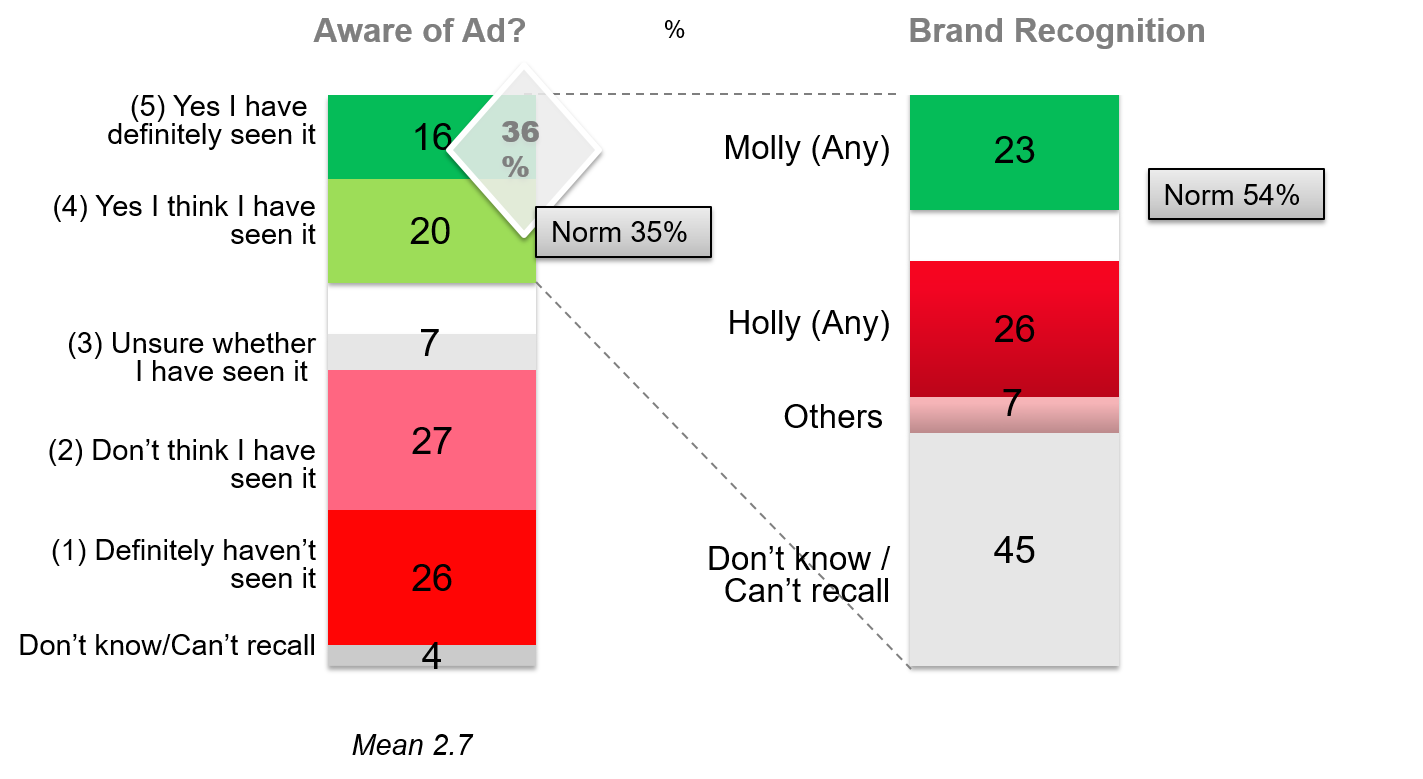

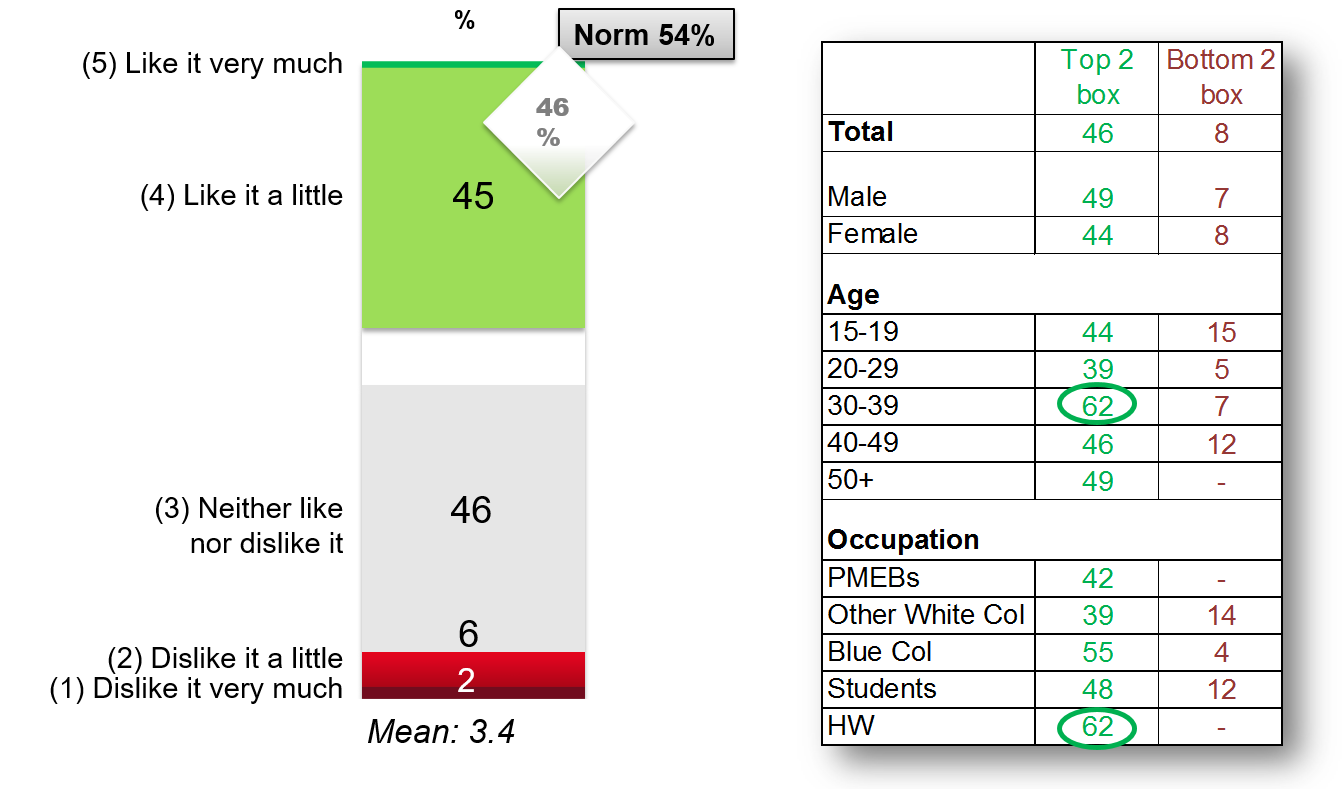

It is clear from Exhibit 5.11 that brand recognition was very weak. Of the respondents who claimed they saw the commercial, only 23% could correctly identify the brand. This is well below the norm of 54%.

Besides, a greater proportion (26%) of the respondents thought the telepic pertained to Holly, the competing brand. This was a major concern, one that made it clear Molly LFHC advertisement was not achieving its desired objectives.

Diagnosis of the advertisement helped reveal the major factors contributing to the lack of performance of the ad.

Disposition towards the advertisement, Exhibit 5.12, was relatively weak. The proportion of respondents who liked the advertisement (46%) was below the norm of 54%, and only 1% claimed they very much liked the ad.

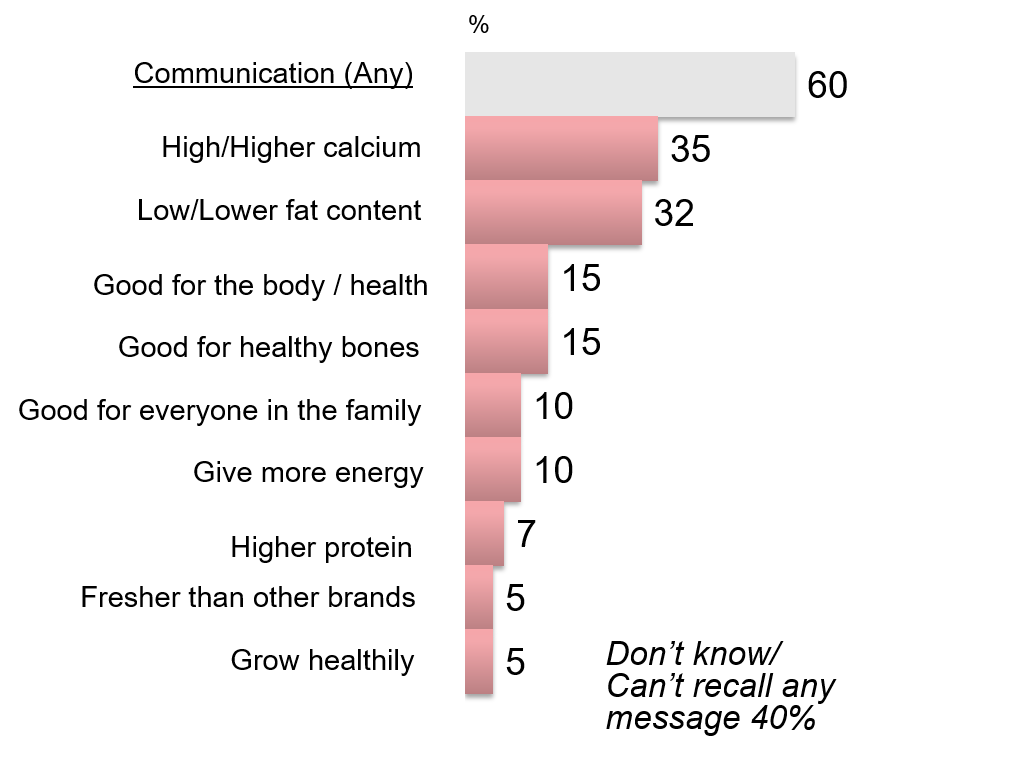

That the spontaneous message recall, Exhibit 5.13, was poor, confirmed that the commercial was not generating interest, and that viewers were not getting involved.

Of the respondents who claimed they had seen the advertisement, 40% could not recall any message. Recollections by the other respondents pertained mainly to generic aspects about liquid milks such as low fat, high calcium, and good for body, health and bones. These benefits were also being offered and advertised by Holly HL, and most of the other major brands in the market.

Importantly, not a single respondent mentioned the intended message — i.e., Holly HL is made by recombining milk powder with water, whereas Molly LFHC is fresh milk.

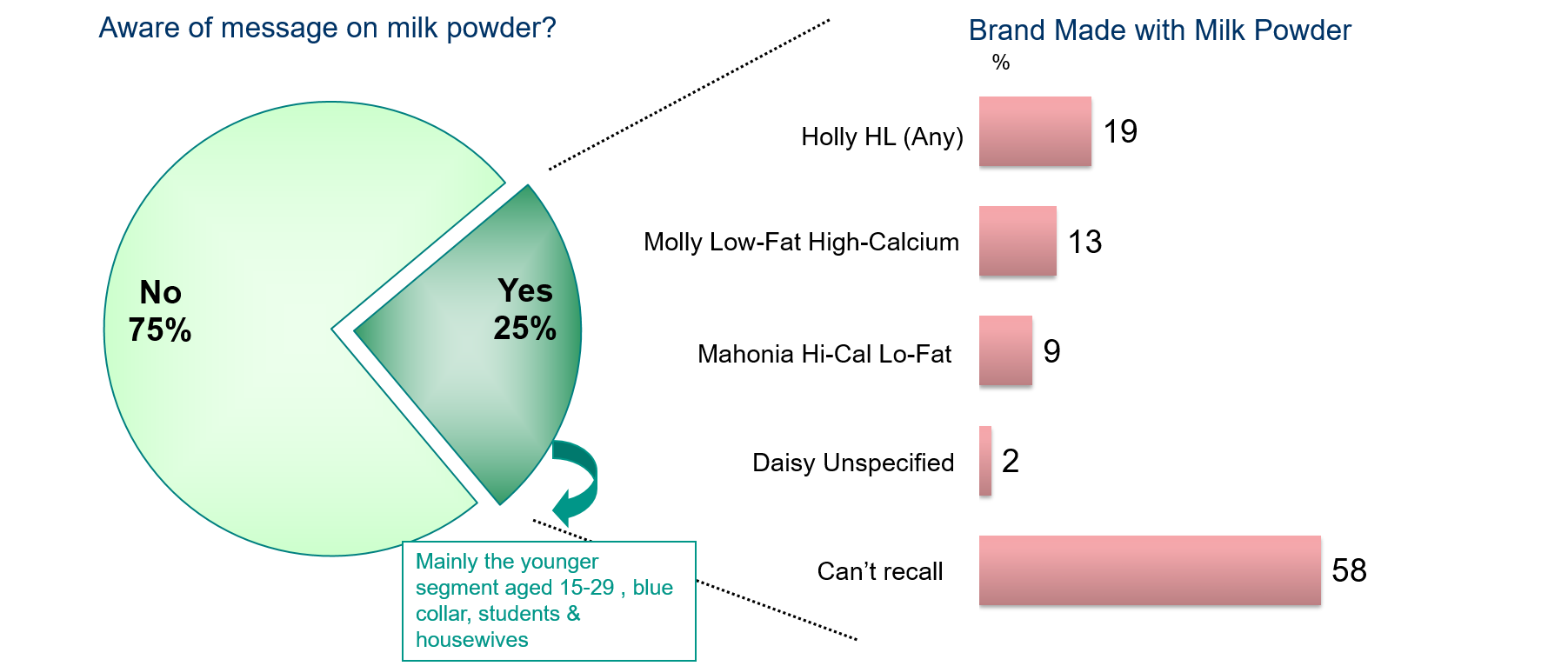

Even when aided (Exhibit 5.14), only 25% of the respondents who claimed they had seen the ad said they were aware the ad’s message was that some brands of fresh milk are made with milk powder. Moreover, a high proportion of these respondents (58%) could not recall the brand name of the recombined milk, and many others incorrectly identified the brand. This proportion alarmingly included 13% who claimed that Molly LFHC was the brand made from milk powder.

One may conclude that viewers did not pay much attention to the advertisement, which is usually the case for advertisements that fail to generate interest.

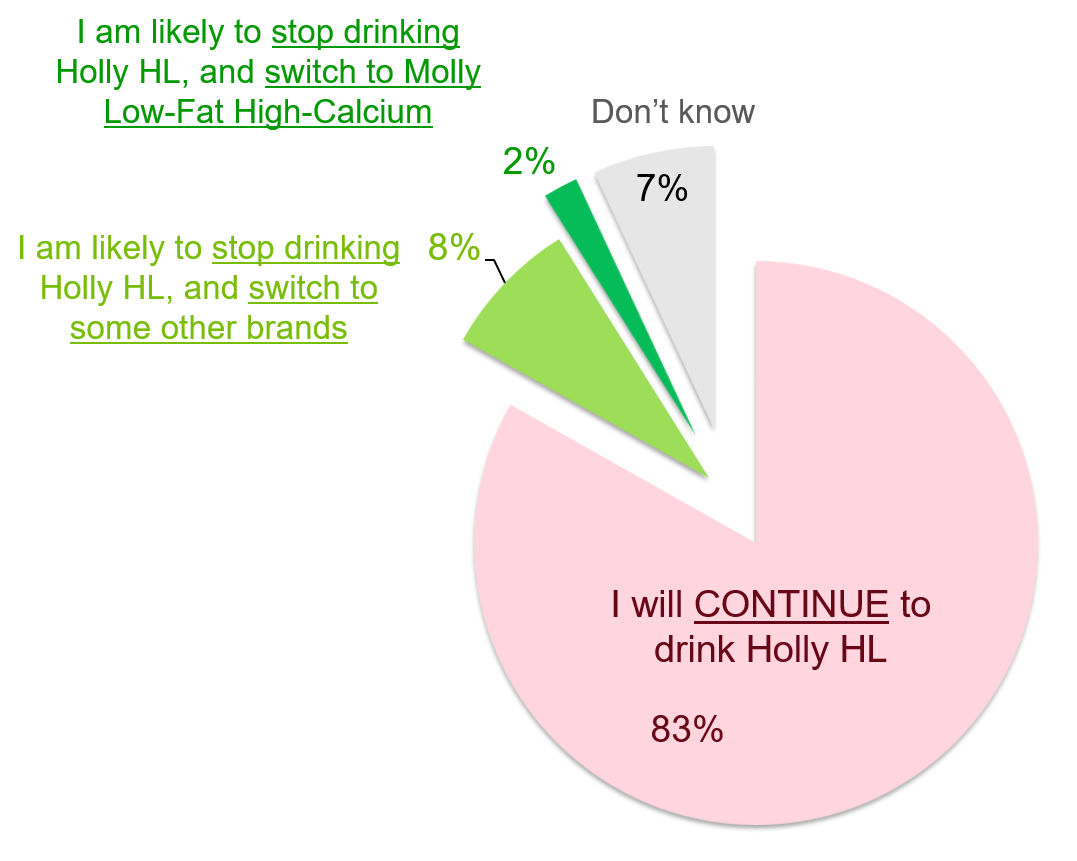

Exhibit 5.16 Claimed behavioural response after intended message of ad is explained. Base — Holly HL most often drinkers.

The objective of the question in Exhibit 5.16 was to comprehend the extent that the tactical approach might achieve the desired objective, if the campaign could more effectively communicate the intended message.

The 2% who claimed “I am likely to stop drinking Holly HL, and switch to Molly Low-Fat High-Calcium” plus the 8% who claimed “I am likely to stop drinking Holly HL, and switch to some other brands” was quite significant. Molly LFHC could gain a share point if it cannibalized 2 to 3% of the 40% share of Holly HL’s market volume.

Though a percent point gain is significant for a small new brand, these findings should be viewed in the context that for such questions, respondents have the tendency to substantially overstate the extent to which their behaviour is likely to change.

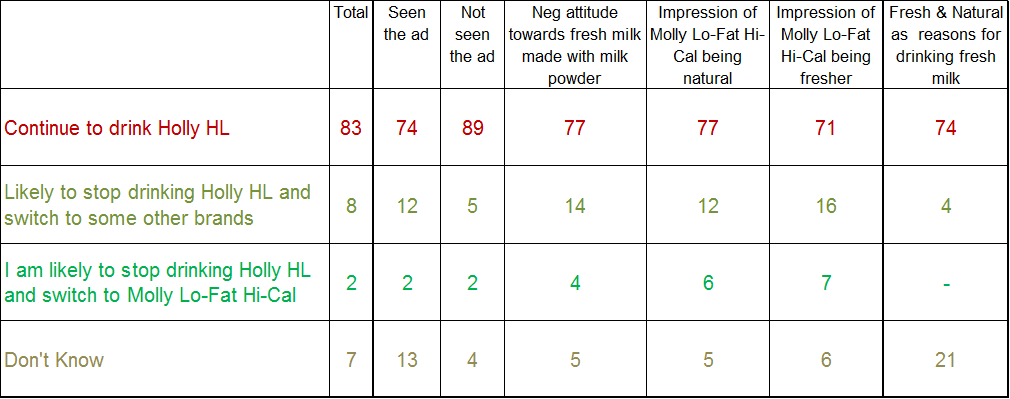

Exhibit 5.17 Claimed behavioural response after intended message of ad is explained. Base — Holly HL most often drinkers.

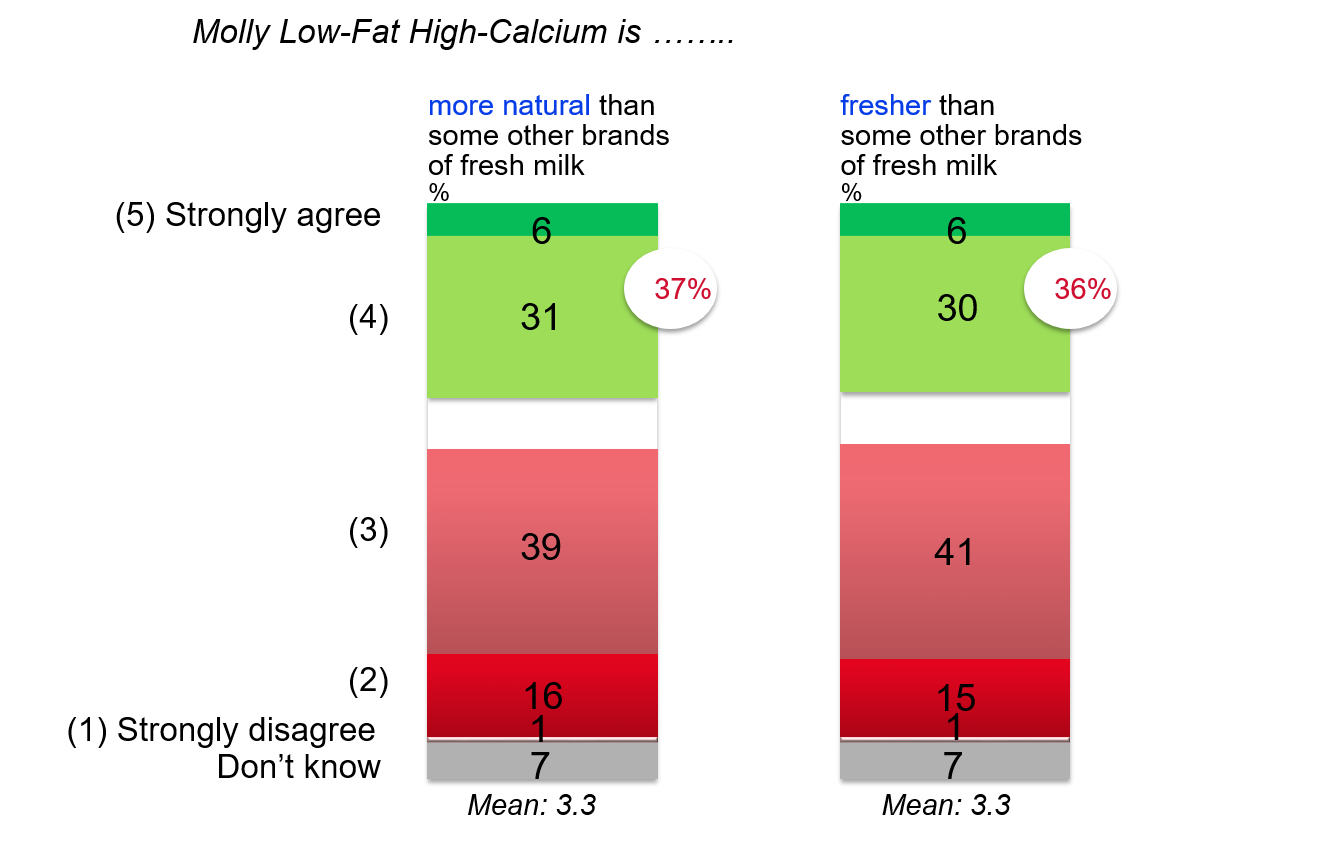

The concluding exhibit, Exhibit 5.17, tells us that those respondents who believed Molly Low-Fat High-Calcium was natural and/or fresher had significantly greater inclination to switch to the new brand. For the tactical campaign to work, it was therefore important that these messages got through.

From Exhibit 5.15 we know that 37% of the respondents agreed that Molly LFHC was more natural than some other brands of fresh milk, and 36% agreed that it was fresher. These proportions will need to be substantially higher for the advertisement campaign to deliver on its core objectives.

Recommendations

Based on these findings, it was strongly recommended that the advertising campaign be terminated.

Salience is weak (5% spontaneous ad awareness), and brand recall is only 23%. Moreover, considering the nature of the ad campaign, the lack of brand recognition is a very big concern.

The ad was also weak on comprehension — there was no spontaneous recall of the intended message, and aided recall was fuzzy and in many cases, incorrect.

The intended message had some relevance. After they were told that Holly HL is made with milk powder, a small but significant (10%) proportion of respondents claimed that they would switch brands. Yet, considering the likelihood of overstatement, and that the proportion of respondents claiming they will switch specifically to Molly LFHC is merely 2%, it was recommended that the tactics used in the commercial be discontinued.